Francis

The war began like this.

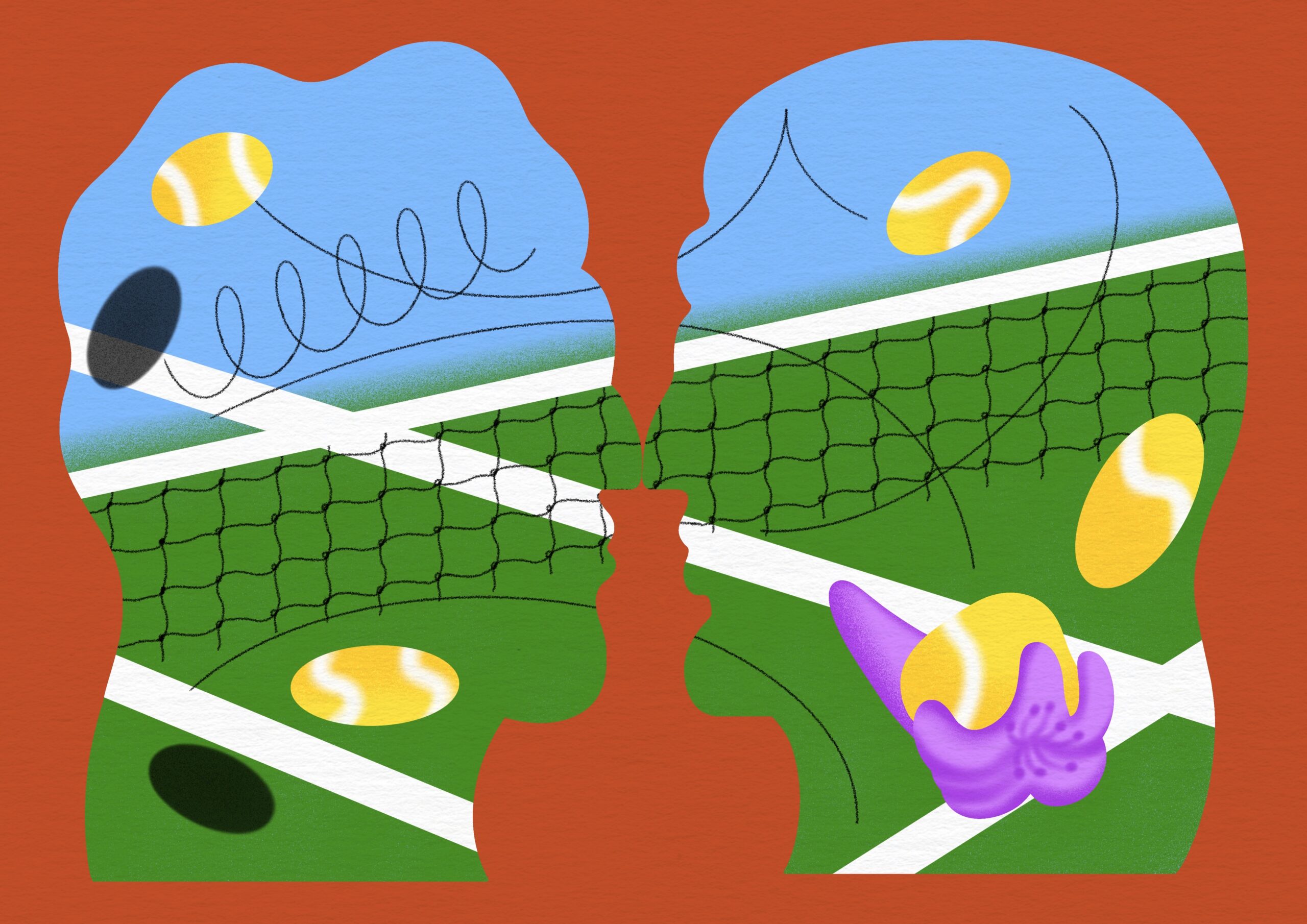

I’d been hitting the courts every day, the ones in Hermon. That’s right, the ones by the dog park, but no, I never went to the dog park cause I never cared about dogs. You see, what I care about is tennis: the sweat, the song, the dance. On the courts, I get lost in the game. Focus on landing my shots, on luring my opponent in, only to fire a fastball back behind their feet. Though I look like a classy casanova, inside I’m still the same chazer fisting his way out of Boyle Heights. If You see, despite what they say, the finest hitters ain’t aristocrats, but thugs.

For two decades I’d been the king of the courts, running them for me and my gang, which wasn’t really a gang, just some Flips, Koreans and Yids who brought beers, leftovers and hit near every night. I’d gotten into a grove, demolishing Morales or Mana, hammering Kim and Park, smashing up that degenerate Sokol on Saturdays and Sundays. Us Yidden preferred the sabbaths, whether we observed them or not, hell, whether it was even ours to begin with.

I’d have ruled them courts until I could no longer lift a racket had that grasshopper not appeared with a basket of balls, a country club haircut, the will of a wolf.

Here’s the law: anyone stupid enough to ask how deep you are, you bark back, We’re just starting. Then hit, drink and kibitz til the whole Megillah gets read. The grasshopper didn’t like that. Would wave away the smoke from my cigarette and complain that it wasn’t ‘cool’ to run the courts. Kids these days need a smack, but I figure, why settle for a smack when I could give the boy a spanking?

That’s right, that’s when the war began.

Jesse

In high school, I janitored at country clubs. Oakwood, Blue Hills, Berkshire. The names made my stomach turn even more than mopping up the rich kids’ vomit during their summer socials. It was a terrible job except that I could use the courts. I’d stay late, switch on the lights, perfect the spin of my serve as the cicadas sang.

The on-staff pro was an old queen, silver-haired, closeted of course because how else would he have gotten the job? He gazed at me as I raked the pool and young Lolita I was, I batted my lashes and begged him for lessons. He wasn’t great, but he polished my game and I didn’t mind letting him paw me for the pointers. By summer’s end I’d weaseled away his prized Wilson and moved to LA.

I started on the courts in Echo Park, but the Mexicans muscled me off so I went to K-Town, but the Koreans policed them like a prison yard. I applied for jobs at clubs and got laughed out of their lobbies. Then I discovered Hermon: glassy around the baselines and sagging nets, but free and shaded by giant jacarandas.

That’s where I met the ringmaster Francis and his circus of sad, old clowns – Mana, Morales, Kim, Park, and Sokol, that creep, who leered at me and fawned over on my ‘boyish, midwestern looks.’ I’d been hoping to hit with the Hollywood types, maybe play my way into a career or the arms of an heiress, but I was new to LA, broke as a church mouse, and grateful to have found steady games, decent players, beers post match.

Except Francis.

The guy would smoke while rallying, a cigarette clenched between his tar-black teeth. Probably thought he could bully me into submission with his brutal backhand like he did the others. But what I lacked in power, I made up for in precision and enjoyed playing fetch with the old hound, watching him chase after shots and though he played it cool, I sensed his humiliation, that beneath his debonair looks seethed a pitbull’s rage.

Things took a turn for the worse when Francis and I played singles. It was match point, advantage in, my serve. The gang reclined on fold out chairs, drinking beers, oldies purring from Mana’s portable radio, Sokol winking at me. I threw a hook and to my surprise it landed short and wide. An impossible shot to return. I’d won.

“Redo!” Yelled Francis.

“Redo?” I asked. “Why?”

“Wrong side of the centerline, kiddo,” Francis said.

I looked for the others across the sun-baked concrete, hazy with heat curling off its surface. Everyone stared into the bottom of their sweating beer bottles. Even Sokol pretended to not be paying attention. It was such a big lie, that the only response would’ve been to call Francis a cheat and storm off. Which I didn’t do. Couldn’t. Figured I’d beat the bastard. So I redid the serve and the grizzly clawed back to deuce and pinned me to the ropes and I slammed a couple of homeruns out of the ballpark and he won off my rookie errors. To celebrate his victory, Francis inhaled a pack of cigarettes and gloated with the others while I sullenly stayed behind on the courts to perfect my serve.

Later I packed up my things and went to my car, only to find the back tire flat. Not just flat, but slashed open.

So a few days later, when Francis pulled me aside and said he’d had enough, best-of-three matches, loser leaves Hermon forever, I smirked like the country club kids and accepted.

Francis

The gang gathered to watch the brawl: Park, Kim, Morales, Mana, and Sokol, that traitor, slobbering all over Jesse between games, spritzing him with water, fanning him with a tennis visor. The others nursed Hites or ate pork adobo in the shade, a flock of parrots squawking in the jacarandas as I boxed the boy out Six-Four in the first round.

Trudging to the baseline, I ignored the broken glass rattling in my chest. Good God I wanted a cigarette. As we sparred, I remembered the days back in Boyle Heights, practicing against the wall in Hollenbeck Park because we didn’t even have courts in the old neighborhood. While sucking down Gitanes, Don Gregorio would drill my backhand, sharpen my slice, call me un judío flojo as he’d yank away my racket and show me how a real hitter hit, the man was machine gun fast peppering balls against the wall, the racket’s head growing so hot that he could light a match straight from its strings. Just like Don Gregorio I thought, sniping a ball deep and coasting to a Four-One lead. The cricket served. Hold him off and things could return to normal, just me and my gang, the courts. Hell, my courts.

The games blurred together and in the fog of war I blew four in a row and wondered if I should hang myself from the ceiling fan later that night.

Four-Five. The boy had the initiative, the blood lust of the Reds roaring towards Berlin in his eyes. He wanted what was mine, which I wasn’t sure I even had any longer.

Why must we fight? I wondered, like every grunt facing the flack.

Jesse

Third match: the courts, the gang, the glory were all on the line.

After I waltzed through the first two games, the jackal’s spirit seemed to break.

Francis looked shaky, almost like he wanted to toss off the crown. I almost backed down, it was just a game. But after months of enduring his ridicule, of figuring out what shaygetz and goy meant, of the slashed tire, I planned to toy with the bull before putting him to pasture.

After landing a couple vicious left hooks, I felt guilty. Francis fighting for air, bewildered, losing track of the score, trying to light a cigarette, only for the wind or his own coughing to blow out the flame. I recalled finding Hermon, how Francis had invited me into his kingdom, only for me to steal it all away.

Francis

I fought my way back to a Five-Four lead and found myself heaving, gasping, on the verge of death, but serving at deuce. Little prick probably still thinks I cut his tire. I’m no patriot, but this country’s youth have gone straight to hell. No matter, two points and I’d put the puppy down.

We tangoed back and forth until the boy dropped one shallow. I moved in, play it close, like a knife fight in a telephone booth.

Jesse

My advantage, match point. If Francis spits out some bogus call again, I’ll go after him with my fists.

I toss the ball into the sky. When I cut it down, I await Francis’ gunshot return. Except, I hear nothing but the parrots squawking in the jacarandas.

Francis is face down on the slippery baseline, a shiver through his hips.

Mana

As the ambulance carrying Francis wails away, the crew circles round. Kim and Park uncap fresh beers, Morales spikes the oldies, Sokol knights Jesse with his Wilson. I sweep away the cigarette butts scattered across the court, pick up my racket, and that’s when the rallying begins.