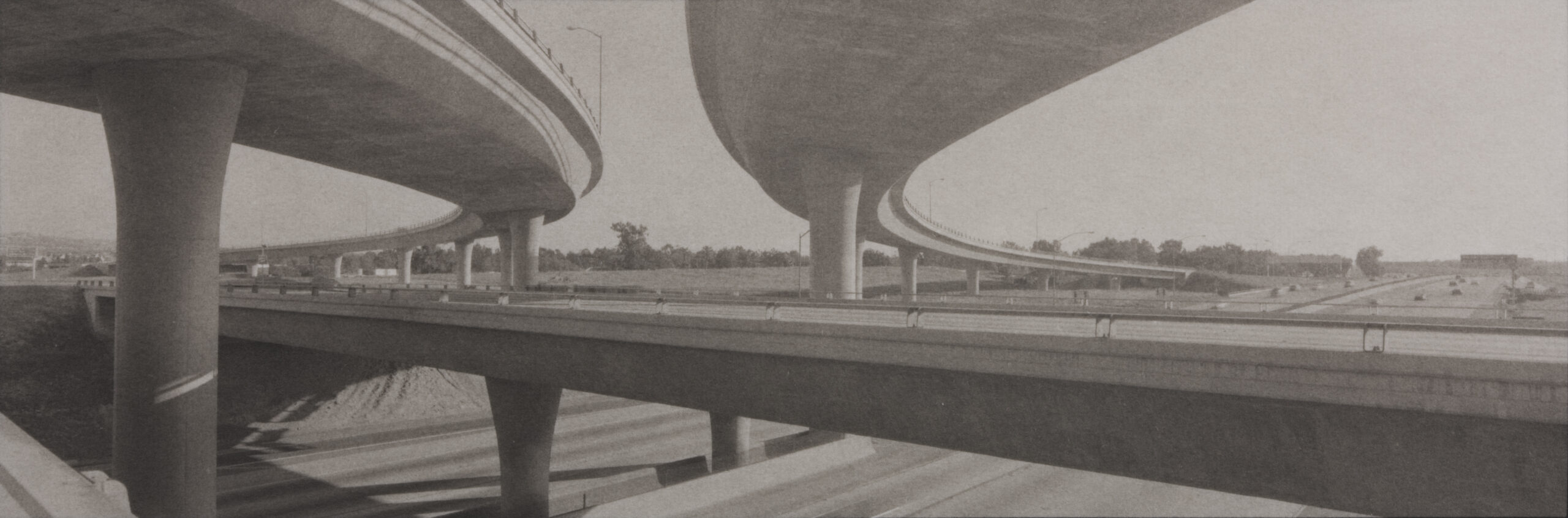

Monuments to emptiness, 2 x 6 inch photographs. Static in the between, static in the wide, arching, not so arching. Layers of freeways curve into one another at streamlined meeting points. Framed by palm fronds and billboards, stone, monolithic columns uphold an atomized life. A value system.

Catherine Opie has said, “The freeways separate communities, but I would say that the biggest thing they do is separate the city from the suburb.”

An invisible divide, made legible by the freeways themselves, and their one, clear imperative: Drive. Only functioning to transport a milieu of vehicles, rigs, and motorhomes from point A to B, skipping the city from above, behind, and aside. Cutting through without knowing the interiority and sheepishness of place.

Catherine Opie’s Freeways series was conceived in 1994, when she began photographing the quotidian structures in the early morning using a panoramic camera. The resulting work is a collection of stranded lines, devoid of context — jutting through the sky, curving into horizon, obviously infinite, obviously seamless.

The freeway is a product of modernity as much as the Brooklyn Bridge, which poet Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote so passionately about during his journey to the United States in 1925.

He lauded the bridge for its steel frame, its miles of cables conjoining austere bolts shaping windows out onto New York City. For him, the bridge held a religious aura; he called it “a museum madonna.” He wrote of men “rant[ing] on radio,” their “hungry howl,” how they “leapt / headlong / into the Hudson” on humankind’s conduit. Its steel a connective plane, as he, too, a visitor from the Soviet Union, “stood [ ]/ composing verse / syllabic by syllable.” For Mayakovksy, modernity was a promise of a unified future, where men met, lived out their lives. Modernity a bridge itself.

For Mayakovsky, the bridge is both a monument and a site of germination, a flourishing: “From this bridge / a geologist of the centuries / will succeed / in recreating / our contemporary world.” People — vitality — at the core of his fascination.

In contrast, Opie’s freeways are solitary, photographed before traffic crowds the pavement. Many of her images are desolate: Roads winding, cursing, cruising through the desert. Brush grows, peaks, wanes into overexposure. Straight lines gash the monochromatic sky, which does not brighten the page — it is the abyss within which a monument excels. At an underpass, columns stand erect as enduring stories, only collapsible by seismic waves beneath their concrete forms.

Although not explicitly noted, I believe Opie must have photographed the twisting Arroyo Seco Parkway, also known as the Pasadena Freeway. The first freeway in the West, it opened in 1940 to connect downtown Los Angeles to the city of Pasadena, setting the precedent for the Los Angeles freeway system model. Supported by the Automobile Club of Southern California, and funded by the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce, Pasadena City Planning Commision, as well as Pasadena Realty Board, it was constructed to better enable commuters’ automobile travel between their workplace in industrial parts of Los Angeles and the pleasantry of their single-family homes in wealthier Pasadena.

“On freeways, there is only from and to; there is no middle or center,” writes Austin Roy of this Winding Arroyo Corridor. Drivers do not interact on the freeway, do not cross one another’s path; skip much of the city.

These freeways were meant to extract and push forward — expand the territory, find a freedom. In a mirage of spaciousness and the myth of an open road, westward U.S. expansion bestowed the (white, European) individual the freedom to own. To extract resources. To place oneself in a self-determined map of history. .

/////\\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\

\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////\\\\////

“The Freeways are the architecture that will be left behind like the pyramids in Egypt,” says Opie. A preconception of what history will look like when it dots the future’s pages. Her interest in photography is “the way the camera can be used as a tool in relation to creating history — 150 years from now maybe there aren’t going to be any more cars on these structures, but the structures will remain.”

Why must the freeways be preserved in the style of the Egyptian pyramids and the Sphinx? Photographed somewhere between the years of 1849 to 1851 for the first time by Maxime Du Camp, they were captured as oddities — excavated, rinsed of meaning. Lifeless. Lonely photographs, fragmented outside of context.

Opie’s gaze casts freeways as static relics to be captured on film and in history books. In her limited view, history is a lifeless entity meant for encasement in museums, framed by the epistemology of European Enlightenment. Opie’s work follows in the footsteps of place dissection and extractive scientific inquiry — like a negative slide placed over the image with double, triple exposures, upholding prosaic ideas refusing structural decay.

What is preserved in the photograph?

A moment. An ideology in fear of its own folly, its death.

What is preserved in a photograph of an American freeway system in Los Angeles, photographed in the connaissance, stylings, and colorations of a 19th century photographer and anthropologist concerned with exotifying structures?

An othering.

Monument etymology: late 13c., a sepulchre, from Old French, meaning monument, or “grave, tomb,” and directly from Latin monumentum, meaning “memorial structure, statue; votive offering; tomb,” literally, “something that reminds.”

It’s baffling to think of the pyramids as empty, desolate structures, photographed without people around, as if epics of a past no longer relevant.

The pyramids are not monuments, but structures. Structures indigestible to modernity’s gaze. Originally built as resting sites — yes, tombs — the pyramids continue to exist with agency, nurturing regeneration, in a cyclical movement akin to Mayakovky’s Brooklyn Bridge.

TOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTOMBTO

A photograph is not only a reproduction of the material. It is a collision of past and present. A framing of knowledge carried over through time,interacting with the viewer’s contemporary perception, while empirically attending to experience through the utility of mechanical reproduction. Art as both instantaneous and as record. It is an attempt at truth.

As a photographer, Opie must be aware of the reproductive nature of her discipline, the interiority of image-making. History is, indeed, created by narrative, form, and image. A propitious conjecture. Otherwise, history just happens. History, with the capital “H” distinction, is people’s daily lives through a lens of grandiose gestures concomitant with — and in resistance to — the state’s desire to control and sculpt language, whittle away at indigestible pasts, the fashions unfit for a cultural agenda. Often, the History one is privy to is enacted in a monument, a national persuasion becoming fact. At times it is resistance abdicated to, assimilating it into stone.

“When we speak of ‘shooting’ with a camera, we are acknowledging the kinship of photography and violence,” writes the photographer and art historian, Teju Cole in a New York Times Magazine article entitled “When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism (And It Still Is)”. The violence Cole describes is a physical violence as much as a violence of representation, literally capturing the body onto a framed image presented as truth. The subject might not have given consent for this act – their subjecthood removed, turned object.

In this sense, maybe what Opie concocts of history through her photographs is her most honest attempt at truth.

With her camera, Opie creates history. She frames and fixes what she sees, how she views life’s splinters. To some extent, perhaps, the solitary, architectural freeways are the representation of an imagined solidity — of moving through the day by driving to what must necessarily be the outskirts of the city — there is a lingering, perpetual reminder of one’s ability to escape into paradisiacal, or perhaps empty, circumstances.

Perhaps freeways are markers of escape, but they are also insults, signs of the dead. What is a freeway without oil? Why even dictate a freeway if there is no product to move, caravan along the road? Industry pushes forward, relentless, granting the freedom to own. Perhaps freeways are grave lacerations in the land. And perhaps freeways are also the seams in a lacerated and divided space. A consumed space. A space, disbursed. The grand, illustrious, elusive land.

In the summer months, scotch broom yellows the edges of California’s freeways, its ditches. A horribly invasive plant, its roots are impossible to destroy once they have taken hold. To hold: from Old English healdan — to contain; to grasp; to retain.

Hold/consume.

Remove.

Photography becomes an act of removal, placing the subjectivity of the individual or place being photographed into the hands, the gaze, the construction of the person or entity on the other side of the apparatus.

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ]

The images of Opie’s I’m drawn to the most are the ones imbued with texture, curve, and contrast. Driving on these deserted roads, I imagine there is room for self-reflection, to glide atop the structures inscribed into the land, into the overgrowth. Where shadows confer with materiality, and the freeways take a life of their own, bleeding their essence — layer and deceit — into the surroundings. Starkly dark freeways against a torrid, grim sky.

Nothing, neither among the elements nor within the system, is anywhere ever simply present or absent. There are only, everywhere, differences and traces of traces.

Sinister, industrial nighttime photos depicting highways. I think loosely of the feeling I get on the Seattle ferry crossing the Salish Sea, riding solo in the murky dark of winter, even though it’s only five o’clock. When the sky is suspended above the sea line. Horizon broken. Hidden in the seams. Somewhere the touch of ultralight vanishes, leaving the shore with weak suspensions of soporific, lugubrious flickering. Where the ocean is aphotic, untouched by light, moving lorries across to the other side. Profitable. Enraged, and sorry.

Some of Opie’s photos feel like hauntings. A regression. Cyclical insignias.

One frame stands out in particular, of columns prefabricated for the raising of freeways. Rows of them in the desert, presumably next to a construction site, waiting to be put to use, to be thrust towards structural decay. A forlorn pantheon; sculptures of the modern age, perfectly aligned, manufactured by uniform assembly line. Scattered rock, dust, and ragged hills surround the perimeter. Footpaths peek through brush on hillsides, next to machinery for fusion or disassembly.

Or maybe this is a waiting place. A graveyard where columns have been banished, as casualties of feeble infrastructure. This photo is eerie, reading like a historical assemblage of abandonment and disuse. These structures are wrought for use, yet here they are, waiting. A discord between installation and utility is woven for the viewer.

What does Opie think of the pyramids, besides viewing them in an isolated, humanless state? How is her belief or view of the past — the modicum that has been recorded — reflected in her own depictions of freeways? Largely a portrait photographer, Opie’s practice of portraying of freeways as subjects and the society dependent on them communicates something – what?

In one photograph, two curves atop the frame diverge at a potential meeting point. The pathways never cross — a bifurcation rendered against an overexposed sky. In this particular black and white distinction, the photograph seems to capture grief, wonder even. Light hits the concrete sides, washing out a stature. How can these be so geometric, architectural, yet almost organic? The curvature. The crevice. The details of weathering.

These shapes, these freeways. Almost accretive productions, growing as the viewfinder draws closer towards me.

Round and round and round. A type of sickening carousel.