A little over 8,000 miles away from me, lives my grandmother. I’ve never gotten the chance to be close to her. Still, I imagine what her days are like. Where her favorite place is, what she keeps beside her bed, and if, when she eventually lies down to sleep, she can also look up at the moon through her window.

I last saw her in my Tita’s home in Palm Springs when I was four or five years old.

The dry swelter of Palm Springs made me love my Tita’s house for how it protected us from the heat. I could always breathe well in that house. However, the time my grandmother was there, my rhythm was disturbed. I didn’t feel like I could eat as much, be as loud, or run through the house quite like I wanted to. Although I knew I wasn’t poorly behaved, the idea of her disapproval seemed overwhelming.

I don’t remember if I spoke to her, only how I peered at her from around corners or quietly from across the table. Even if we had spoken, the language barrier and my little age probably would have led to a pretty inconsequential conversation. When my dad spoke to his mother, I didn’t understand what they were saying and no one felt any urgency to translate. But every time we met eyes, I remember feeling immense, maybe discomfort, but hopefully, connection. I did not understand her, but I think, and I hoped, she understood me.

As I grew older, I often wished that I had made better use of our shared time in the Palm Springs house, and asked her more questions. Even better, I selfishly wished she lived here and we could share our days. I didn’t want to have to wonder about her.

In 2020, hate crimes against Asian Americans in America rose by 145% compared to the year before, according to a report by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. On March 16, 2020, a surge in hate incidents occurred after Donald Trump tweeted nonsensical praise of American industry — which included the term “Chinese virus.” In response, the outcry from the Asian diaspora community gained traction and organizations such as the Stop AAPI Hate coalition arose. During this time, I was happy to not know what it would be like if she lived here with me.

Valuable work continues to be done by groups such as Stop AAPI Hate, yet — as someone who has spent the majority of their early adulthood online and politically engaged – the word “anticlimactic” comes to mind. The hollowness of the mainstream discourse comes neatly summarized in a video VICE posted titled, “Asian Americans Debate Model Minority Myth & Asian Hate,” as a part of their “VICE Debates” series. As the video was masticated by the discourse machine, it snapshotted how the Asian diaspora sees themselves in mainstream political spaces. The group debated the “model minority myth,” they spent most of the time just getting past the definition of the term. Even those who came with a more progressive politic frequently got caught in discussions of imposter syndrome, “representation,” and whether the Indian community did not “claim” Kamala Harris because of anti-Black racism or because “she decided to present more Black.”

Conversations, both by viewers and by participants in the debate, were rarely able to lift the conversation out of the pitfalls of what is frequently called “boba liberalism,” an ideology capturing an Asian diasporic zeitgeist consisting of sanitized and trope-ified versions of Asian immigrant experiences. In the most popular digital destinations for the Asian diaspora in America, from Facebook memes to NextShark news, Asian lives and experiences are reduced to tiger moms, Kumon, and “ethnic” food. It’s not that all of these things are insignificant to Asian American culture, it’s that when removed from their context, they become the puzzle pieces to the image of a model minority. Wealthy, studious, and dutifully working themselves up the “system.” An image that only captures a hyper-selected group curated by compounding immigration restrictions, particularly in the U.S. and Canada, that looked for “high-skilled” labor. With the social, economic and political resources this small group of Asian immigrants have, they are able to write a narrative, primed for the market, on behalf of all other communities lumped into the varied and diverse “Asian American” label.

A notable feature of this declawed version of the Asian diaspora is the “stinky lunch” story; the experience echoed throughout the community of bringing ethnic food to white school cafeterias and consequently being at the receiving end of endless racism and xenophobia. Often treated as the pinnacle representation of our othered-ness in America, this story is frequently followed up by the “success story” of how we overcame this racism. This success is almost always tied to material wealth.

To boil down Asian American oppression into childhood bullying perfectly exemplifies why much of the current discourse seems to fold in on itself — there are no meaningful or current connections to class, bodies, or displacement — it lacks our context. This is not to diminish the experience of being rejected and ridiculed by your peers at such a young age. What we experience as children is poignant, yes, but those experiences are merely symptomatic of our oppression. We must ask, in the recitation of this story as adults, are we working to understand why these white children behaved the way that they did? The “stinky lunch” sees itself reflected in some of the succeeding conversations around Asian hate, as Asian Americans came forward online and shared their experiences of discrimination — many taking the form of verbal harassment. No matter how violent these instances may be, the incident in and of itself is not our entire oppression. The wave of hate crimes that followed the COVID-19 pandemic is a continuation of systems of oppression that have not only affected diaspora populations, but echo histories of colonialism and U.S. imperialism that have devastated our ancestral homes. Every time “China” was uttered by Donald Trump’s thumbs, he invoked America’s centuries-old power over the perception of the region. Nothing of his own creation.

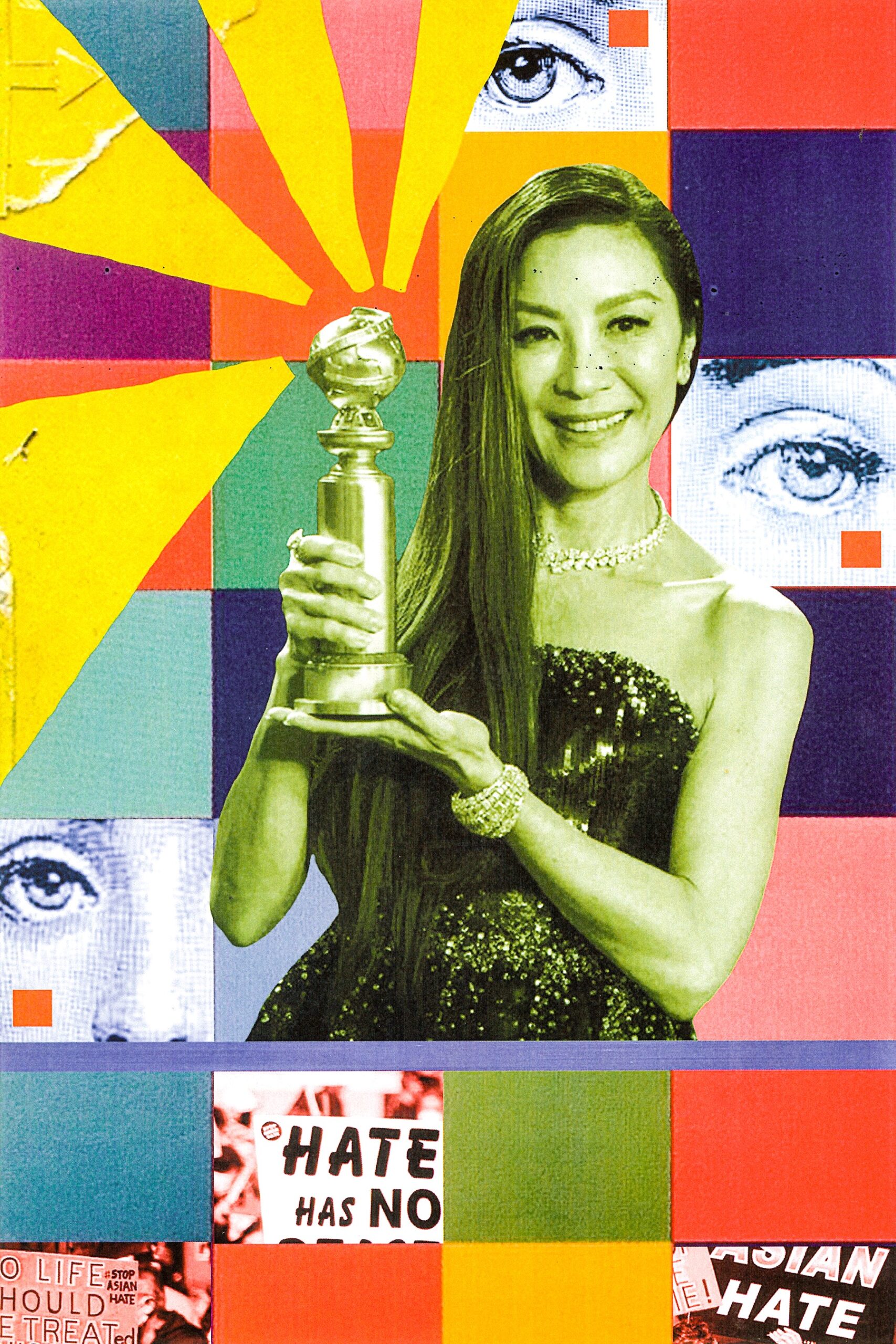

During this same time, American culture has been experiencing the perfectly cognitively dissonant moment of Asian excellence in film and television. When Parasite became the first international film to win Best Picture on February 9th, 2020, so began what Time magazine called “a new era in film.” I better knew it as the beginning of my era of being a person that cried at awards show thank-you speeches. To see stories as exciting and true as Minari, Squid Game, PEN15, Pachinko, and most recently, Everything Everywhere All at Once stirred up something in me I didn’t have a name for. Yet, each of these pieces of media exist in an industry predicated on protecting white supremacy and racial capitalism.

Everything Everywhere All at Once won Ke Huy Quan his first Golden Globe, leading to his incredibly emotional thank-you speech. For those who haven’t memorized it yet, in his speech Quan thinks of the start of his acting career as Short Round in Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom. After The Temple of Doom, Quan experienced a more than 30-year drought in his career which he spent wondering if he, “had nothing more to offer […] never surpass[ing] what he achieved as a kid.” Quan then proceeded to thank the directors of Everything Everywhere All at Once, the Daniels, for giving him the chance to try again.

In response, American blogger Phil Yu tweeted, “I gotta say though, Hollywood patting itself on the back for Ke Huy Quan’s comeback, as if Hollywood wasn’t responsible for the circumstances that made him give up on his acting career in the first place, is pretty hilarious.”

Quan’s speech went viral, with Asian Americans on TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter tearing up right alongside him. And even though I was definitely one of those sniveling retweeters, I can’t separate the power of this moment from its reality. The year that the Golden Globes returned to television after being criticized for not having one Black member of the Hollywood Foreign Press, and two years after it received criticism for categorizing the American-made film Minari as a foreign language film, the awards show’s most viral, commodifiable moment was rooted in the pain felt by a Vietnamese man after facing anti-Asian racism that prohibited him from meaningfully working in his field for over 30 years. Our pain, once again, was stripped from its context and sold right back to us in a form more palatable for white audiences.

The “stinky lunch” story, and its components of come-and-gone experiences of racism, dutifully working hard, and patiently waiting for our turn to “try again,” has become a staple of the Asian American experience. It has become a trope, and when we treat Hollywood as the highest stage for our stories to be told, it becomes a commodity. We’ve sold our story, our parents’ story, and to do so, we extracted every thread of revolution, oppression and liberation.

When I’ve thought to write something, to do something, against the oppression my community faces, I often felt ill-equipped. For guidance, I looked to my peers in other struggles, for Black liberation, for Indigenous sovereignty, but I could never seem to muster the right words. Until I realized that what I, and many in the Asian American community, were missing weren’t the right words, but the right context.

During the late March, early April season of 2021, 75-year-old Xiao Zhen Xie had the internet’s searing spotlight on her after she faced a horrible, racist attack in San Francisco’s core. Only minutes after attacking Ngoc Pham, a Vietnamese man who had been walking nearby, a 39-year-old white man punched Xie in the face while being chased by security guards.

A video was taken almost immediately after the attack, sourced and tweeted by KPIX reporter Dennis O’Donnell, and was the vehicle for the story’s virality. The camera bends around a historic San Francisco light post to follow Xie; in one hand, she hangs on tightly to a wooden board and in the other, a paper towel to her bleeding eye. Initially, she shouts in Cantonese in the direction of her attacker while he sits strapped to a gurney, then at the paramedics, then at the crowd. At this point, the camera pathetically follows her attacker as he is pathetically wheeled away — and Xie begins to wail.

Xiao Zhen Xie’s attack took place the morning after a white man entered three Atlanta spas and killed eight people, six Asian women, reportedly telling police that his “sexual addiction” spurred his attack. Xie wailed, as the families of Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Soon Chung Park, Suncha Kim, and Yong Ae Yue wailed, as the Asian diaspora wailed. I did, too — as I knew them — even though I didn’t fully understand how I did. I won’t say that I imagined my grandmother in this position – I didn’t. The “it could happen to anyone mentality” does not heal a community. It does not matter that it didn’t happen to me, it happened to her — so it happened to us. What I did wonder was what my grandmother would say. If she lived through this, what would she think to do?

What made Xie’s story go viral was that after raising close to one million dollars on GoFundMe for her recovery — Xie decided to donate around 90% of it to the Asian Community Assistance Association. According to the update on Xie’s GoFundMe page on March 23rd, 2021, written by her grandson, Xie stated that the issue at hand is, “bigger than her,” going on to say, “we must not submit to racism and we must fight to the death if necessary.” I’m not sure if this would be my grandmother’s exact suggestion, but I think that I will follow it for her, to protect all of our imagined days.