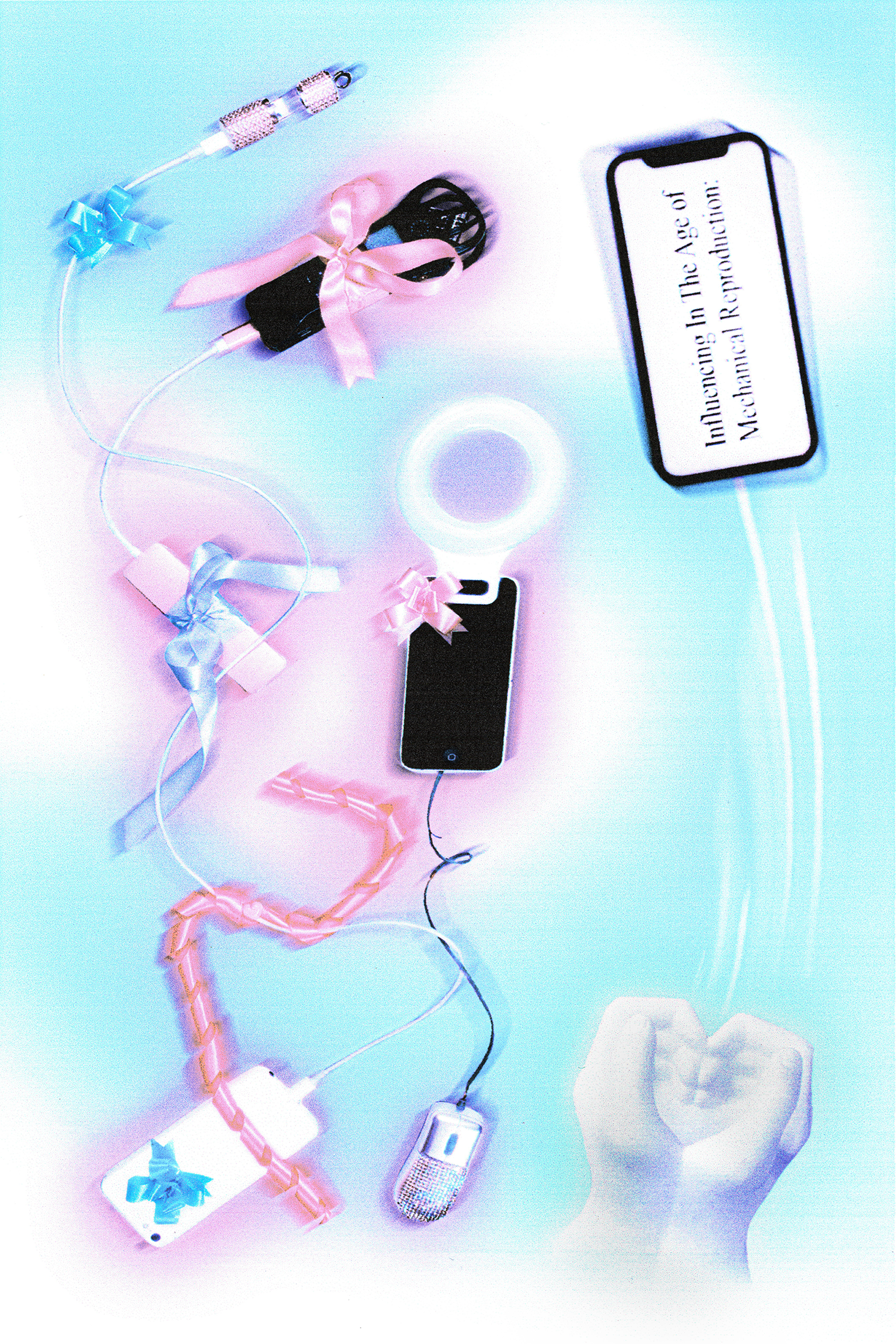

As you enter the world of @LoveDoveClarke, you will smell Maison Margiela’s “Springtime in the Park.” You will taste an organic coconut milk matcha and you will feel ballerina-pink chiffon between your fingers. You will encounter a meticulous visual diary depicting a landscape best described as, “if Petra Collins went to Equinox.” It is frilly and pastel, filled with beautiful women and beautiful pastries. Sponsored posts advertise discreet vibrators, Selkie dresses, and organic tampons delivered by GoPuff. Dove’s hair is always pristinely done, her skin always glowing, the lighting always soft and flattering. Of course, the artifice of this world is evident to Dove and her audience; she makes no qualms about the staging of her photos. In one post from Tuscany, her caption reads, “(yes i photoshopped the scooter to be pink and sparkly because this is social media and nothing is real here) <3.” Dove’s Twitter, on the other hand, is largely unfiltered; her bio reads, “dove clarke’s Online Public Diary,” and she treats it as such. She tweets about her day-to-day life, her relationships with her friends, her sex life, her boob job, her grievances with the world, her passing thoughts. Her Twitter account is relatable, light-hearted and largely in jest and her tweets about the more mundane aspects of her life regularly go viral.

I first met Dove when I was sixteen and attending a pre-college program operated by Maine College of Art in Portland, Maine. She had a room at the end of the hall, a quiet poise I found deeply intimidating, and the same unshakable natural radiance that would fuel her career. Seven years later, we sit on opposite sides of a Zoom call.

Dove initially describes herself as a 23-year old, Los Angeles-based content creator, before correcting herself, “But I don’t know, I feel like the words ‘content creation’ just sucks all the soul out of like what you’re actually doing.” Instead, she offers the term “visual storyteller.” Early in our conversation, we talk about art school, video art, and performance art — Dove spent several years in a BFA program for Kinetic Imaging. We discuss Alex Bag, a video artist whose piece Fall ‘95 follows a New York City art student in the form of a wry, Real World-style video diary shot on VHS. Dove cites the importance of “seeing how completely unafraid these artists seemed to be doing just anything, talking about anything, making people uncomfortable, talking about feelings that nobody wants to talk about.”

I ask Dove about the dichotomy between her seemingly unfiltered Twitter presence and the hyper-curated aesthetic of her Instagram, but shortly after I get the question out I realize how silly it is. Both accounts are curated — one to be “authentic” and one to be refined — and both accounts use the process of curation to define the persona that is @LoveDoveClarke.

“They’re both like an extension of the self. I mean, even my Twitter persona, it’s not the full scope of who I am as a person. Obviously, I can’t put down every thought I have on the internet or give my every opinion.” She pauses, considering her words, before continuing, “I honestly do feel like the character I play, everything that I put out is for her, for my authentic self. You only get so much from an image, you know?. You can’t really get the entirety of a person from an image alone. So, I decided to make my diary public.”

Like Dove, I’ve made space for myself on the internet, though to a much lesser degree. As a teenager, I ran a nominally successful Instagram meme account under the handle @paperbagbyfionaapple, where I’d post about Noam Chomsky and Sufjan Stevens and taking Lexapro. More recently I’ve dabbled in virality on TikTok and Twitter, and I currently write a blog with somewhere over 10,000 subscribers. I’m not poised and radiant like Dove, but I understand what it’s like to make things in your own name for an involved internet audience, people who expect you to fill a certain niche of attitude and imagery that may not be fully accurate to who you are as a complete person. I find that my own online persona is closest to the persona I slip into at big parties or meeting friends-of-friends, some version of me that can be described in a dozen words or less, not so much sanitized as it is caricatured.

Dove’s social media chronicles years of her life: relationships, break-ups, vacations, embarrassing moments, a car crash that left her in the hospital. There is a narrative, a plot that @lovedoveclarke follows, it is a digital archive of her life in which she is the main character. Dove’s online presence lives in a space that is mostly real, it is constructed but openly so. This transparency about artifice and authenticity strikes me as an incredibly literary project, a follow-up to the confessional movement of Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, and Sylvia Plath. There is something fundamentally epistolary about her social media, each post a missive, sealed in lines of code and meta-data in lieu of wax stamps, sent into the world in hopes it will find a sympathetic reader.

In the 2013 essay, “Neo-Confessionalism: Whose Commodity Am I Anyways?,” author Virginia Konchan writes that the “liberation rhetoric of commodification theory — taking oneself to market as the path to economic parity — only applies when the subject retains private control of her productive capital: freedom through market activities is a tough sell for subjects whose only form of ‘private property’ is their body or powers of self representation.” Konchan understands the economic necessity to perform for market demands, which includes the performance of vulnerability or “rawness,” but I’d contend her equation of “audiences” with “markets.” There is market value in performing — and thus selling — trauma, intimacy, and access; particularly for institutions (the expectation to concoct a sob-story of marginalised adversity for college admissions, a contemporary art museum displaying graphic images of police brutality against Black people). But the structures of the internet have allowed creators to interact with their audience on a more immediate level — artists do not have to create art that will serve an institution’s evaluation of what value their work might generate, instead meeting audiences directly.

Dove’s personal brand is just that — a brand. Beyond the individual commodities and images in her posts, it is defined best by its intentionality. The process of playful curation is fundamental in her relationship to her audience, her social media output, and — perhaps most importantly — herself. Over and over, our conversation returns to the idea of fantasy and invention, the internet persona as a process of creating not only a character but a whole geography of desire and fulfilment.

“I like to create my own fantasy world where I can exist as this polished, most presentable, most likeable version of myself. So I create a space online for that person to exist, that person that I created.” She notes that her positionality as a femme, Afro-Indigenous person is important to her, but at the same time she wants to be able to exist as she is as a human being rather than as a voice for an entire community. “I want to make room for myself to exist, however I am. I’ve always felt like I was on the outskirts of everything, my whole entire life. So I’m like, if I’m gonna be out there, I might as well make a space for other people like me to join me. This is what I want to be and this is what I’m going to be, and what are you gonna do about it? Nothing. I can exist in whatever space I want to, without any help.”

The process of actively becoming the version of yourself that exists on the internet is not only the product of choice, but also prescription — creators build relationships with their fans, allowing them social and often financial capital, and in turn audiences come to expect something of their creators.

I spoke with Eliza McLamb, who describes herself as “the co-host of a podcast called Binchtopia, an indie musician, and a writer in many forms.” When I asked about the distance between the Eliza I’m speaking with and @elizamclamb, she replies, “It’s become almost second nature to me to develop this sort of curated version of my own self. Which I find kind of jarring to realize, that this is kind of a tough question because I don’t normally like to put too much conscious thought into it. I assume by now it’s just all sort of subconscious.”

I wonder if there is anything that her audience wants her to be, something people tend to project onto her and her work to fit a pre-existing image they have in their head, if she (or any of us) get to build our personas or if they are built for us. Her oeuvre is deeply personal and confessional, spanning across media like music and nonfiction and podcast polemics. With over 385,000 followers across Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok and a podcast with over 7,000 paid subscribers, she holds a place in the internet’s imagination as witty and thoughtful, self-assured yet humble. If you search McLamb’s name on Twitter, you’ll find posts like “which man do i need to eat to worm my way into the rayne fisher-quann eliza mclamb friend group,” a screenshot of the lyrics to McLamb’s song “Salt Circle” paired with a screenshot of the lyrics to Taylor Swift’s “seven,” and “I know they always joke about it but the binchtopia pod girlies really are my parasocial besties.”

Because of the emotional and complex nature of her artistic output, I ask if McLamb is ever placed into a reductive “Sad Girl” archetype. She says that the notion that writing from a place of sensitivity and vulnerability is somehow self-indulgence or navel gazing is “at odds with why I write things, and why I know a lot of other people write things, which is to connect with other people. And that’s [proven]every single day by even people who sort of misunderstand where we’re coming from — girls who are like, ‘I’m in my Fleabag, Rayne Fisher-Quann era.’ Even that is still a connection and a deeply feeling part of that person who’s connecting themselves to the work, which to me just [disproves]the entire thesis that women make art to be self-serving and wallow in their own sadness, and create this toxic audience of women who are also secretly looking for reasons to lay around in bed all day.”

McLamb’s comment resonates with me — this idea of public vulnerability as a form of action — not just for women, but for people across marginalized experiences. In my own work, I write about some of the most difficult parts of my life: being bipolar, chronic anorexia, being sensitive to a fault. The most impactful aspect of my relationship with my own audience is the idea my readers feel their experience is recognized and articulated. In 1985, Audre Lorde wrote the essay “Poetry Is Not A Luxury” about how emotionalism, and particularly confessionalism, are radical and necessary tools to empower marginalised voices. She speaks against the violence of Whiteness and masculinity, institutions whose aesthetics are based on the cold logic of Enlightenment-era philosophy which dictates that all things must be scientifically rational, packed into linear narratives and bound together with empirical observations. Rawness, intensity, intimacy… these things function as active opposition to dominating power structures when shared, both publicly and privately. Lorde writes,

“For within structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive. Kept around as unavoidable adjuncts or pleasant pastimes, feelings were meant to kneel to thought as we were meant to kneel to men. But women have survived. As poets. And there are no new pains. We have felt them all already. We have hidden that fact in the same place where we have hidden our power. They lie in our dreams, and it is our dreams that point the way to freedom. They are made realizable through our poems that give us the strength and courage to see, to feel, to speak, and to dare.”

Lorde’s words ring with truth and political urgency. Yet still I worry that the desire to participate in a “moment” of vulnerability can overshadow the content of my work, both for myself as an artist and for my audience. Konchan’s critique of neo-confessionalism weighs heavy on my mind, and I’m never sure if I’m articulating my truth or just selling access to intimacy and immediacy. In my own head, I call this the Proper Noun Market: the contingent of social media users who recite the names of authors and intellectual properties in lieu of building their own identity. Later in our conversation, McLamb states, “If people are a fan of an artist now, it’s less that they’re watching from the sidelines and being like, wow, very cool. It’s more as though they feel that they’ve bought stock; like they’re now like a shareholder in that artist.” I ask McLamb if she ever feels that Binchtopia is used as a social signifier in the same way that people use Lana Del Rey and My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Mitski and Joan Didion and Dior lip gloss.

“I don’t think the podcast or my music is quite popular enough to have its own place in the zeitgeist. I mean, to a smaller extent, yes — one thing that people have said frequently about Binchtopia is that it’s like Red Scare, but for people who have good opinions, or like Red Scare for like Girls Who Think or something, which is really interesting. I’m like, it’s just two girls talking. The only throughline that I can really connect is that it’s just two separate podcasts where women are speaking.” I laugh, thinking of the painfully trite practice as seeing “woman-written” as a genre in literature and music. McLamb goes on, “And I’m like, that’s interesting. But I think the function of that is Red Scare is seen as something that’s subversive and cool and like underground — I mean, hopefully less so, recently especially — but the danger in saying ‘I like Red Scare’ is that they have pretty shitty politics, so it’s like, ‘No, look, I still am cool and I’m interesting and I know these things that like other people don’t know, but I’m also not a bad person.’ And I think having a podcast that has a social justice, leftist political lean to it… I mean, it’s hard to draw the line, right? Between oh, are people sharing this episode because they think it genuinely has meaningful information and want other people to learn, or are they sharing it to say, ‘Look what I like, all these things that I know about that that you don’t’, which I think is a behaviour that we all engage in online.”

Alex Goldman is particularly aware of how podcasts and their hosts fit into narratives concerning community and the business of manufacturing online personas. From 2014 to 2022, he was the host of the now-concluded wildly popular podcast, Reply All, but when we speak, he describes himself as “a journalist first and foremost.” In fact, he introduces himself twice: once as, “Alex Goldman: journalist, podcaster, burgeoning Twitch streamer under the name @tuffshed, and sometimes musician” and again as, “Alex Goldman: a person who has a life outside of all of those things that bleeds into that world.”

Unlike Dove and McLamb, whose income is derived from contract work and monthly subscription fees, Goldman’s position came with a salary and a contract from Gimlet Media, a digital media company acquired by Spotify in 2019 for 230 million dollars. Reply All was a journalistic endeavour, but also a business venture, one that came with producers and advertisers and hosts who all knew its success came from the images of its stars. To capitalize on the successes of the podcast, Goldman must play the role of Alex Goldman From The Podcast Reply All, which required not only creating a public persona but also creating a relationship with his co-host that was mostly based in truth.

“It’s very hard to delineate where the me ends and the Alex of the radio begins. I mean, there’s a certain heightened… I’d overplay emotions for dramatic effect. My former co-host and I had a very antagonistic relationship on mic, much more so than it was off mic, and you know, we got so in our heads about how antagonistic we should be toward one another.” Goldman reflects, “We didn’t always calibrate it right, and sometimes people would listen and be like, they’re just being mean to one another. But it was us and our senses of humor and our personalities, but also a performance.”

The medium of podcasts and radio is one in which personalities are detached from their faces, making them malleable in the eyes of their audience. Goldman explains, “People can project a lot of images on me and my personality and my work and what the world of the stories I make looks like. I think the audio medium lends itself to people projecting that stuff onto you. And I think it has [benefited me] in a big way.” Immersing themselves in the world of Reply All allowed audiences not to simply witness the relationships and successes of the show but to participate in them alongside its hosts. Building a sense of community where an active relationship exists between content producers and their fans is, then, a necessary part of market survival. And part of creating those strong, meaningful relationships means that some individuals will overstep the boundaries creators hope to establish. Goldman explains that the existence of these parasocial relationships, “is, in a perverse way, success. Because what I want from people is for them to identify with me and feel a strong bond with me. That is me doing my job well.”

This sentiment is nearly identical to how McLamb described her relationship with her audience, seeing these strong emotional bonds as a success. However, it also requires her to further take on a character or play a role, highlighting the artifice between audiences and nonfiction creators.

“I want to really clarify that it’s really normal to have these kinds of relationships and these kinds of connections, but it does make me uncomfortable to have a bunch of people feel that they know who I am. I think part of my online persona is trying to constantly assert that you don’t know who I am, and we’re not personal friends, and that everything that I put online is not totally the truth. And in fact, I said that in a podcast episode one time. I was like, yeah, sometimes I’ll embellish stories on the podcast, or I’ll make up a little white lie.” McLamb speaks earnestly and mindfully, “And that’s sort of partially to protect myself because I don’t want to give everything away and I want to maintain sort of an air of mystery — that I suppose would’ve been better maintained had I not said that, because people would not know.”

This comment was not received equally by all fans of the show, with many expressing a personal sense of betrayal at the boundaries McLamb seeks to establish, further affirming McLamb’s decision to actively put distance between herself and her audience. But much like Goldman, she understands that these strong relationships are indicators of creative success.

“I just need to realize that everyone who has a connection with me online, ultimately for them, I’m a collection of their own projections. If they’re looking for a friend, I can be that. If they’re looking for an annoying girl online to be mad at, I’ll be that for them.” Dove is confident and self-assured, and I am impressed by the matter-of-factness of her observations. “And the more I’ve disconnected myself and said people are gonna have whatever relationship they want to have with me, and that’s none of my business, the more I’ve been able to just like, post things that I like, think are funny or smart or interesting. I’m not having to engage with that as much as I did, because it definitely did take over my mind a little bit.”

Perhaps there’s something about “creative spaces” that necessitates this Roman à Clef relationship with the truth; Los Angeles has Brett Easton Ellis and Eve Babitz, New York has Dorothy Parker and Eileen Miles, even Berlin has Chris Kraus and Christopher Isherwood (who would go on to apocryphally re-write himself as radically political in Goodbye To Berlin, the source material for Cabaret). On Monday and Wednesday nights I go to Soho House Berlin and order french fries and extra-dirty martinis because they’re half-off. My day job pays around $23,000 a year after taxes, and I’ve started carrying business cards with Siberan wolfhounds on the back that describe me as an “artist and writer” with “berlin-london-new york” written below my name. No one mentions that the building used to be the headquarters for the Hitler Youth. I eat the green olives in my cocktails and I wonder if treating the traumas and accomplishments of my life as plot points for tens of thousands of readers affords me clarity over my experience or distances me from the physicality of my life, and then I realise that eating martini olives and pontificating over the historiography of my writing and myself is very Carrie Bradshaw, Hannah Horvath behaviour. I feel guilty about this too before remembering that Bradshaw and Horvath were both stand-ins for their creators. It’s much easier to sell characters than nebulous, self-contradictory, real-life people; giving yourself up to audience interpretation protects your sense of interiority and increases your market share.

Like Sunday morning cartoons, audiences come to expect a production to be formatted a particular way, for its characters to behave in a particular way and for them to exist as the same personalities they are imagined to be. While plenty of people understand that creators are complex and multifaceted human beings, many audiences simultaneously experience a sense of betrayal as things change. It takes time and effort to connect with a work of art or a piece of media, vulnerability on behalf of both audiences and creators, and with that intimacy comes a trust that can be broken when expectations are not met. After all, if the success of Reply All came from its hosts inserting themselves into the narratives they reported on, how could audiences not insert themselves in the world of the podcast?

There is a distinction between being a “persona” and a “character,” the former implying an individual who has curated their public-facing image and the latter implying a fictional being embroiled in some sort of plot or event. To become a character is an inherently dehumanising — though not necessarily demeaning — process, one that most people do not choose for themselves.

In 2022, Reply All became an event. After Reply All had released two episodes of what was planned to be a four-part series concerning the alleged hostile working conditions at Bon Appétit, a former Gimlet staff member posted a Twitter thread alleging a “near identical” racist, anti-labor environment at the media publishing company. Vogt and Reply All producer Sruthi Pinnamaneni were accused of anti-unionization efforts (in the same Twitter thread, Goldman is described as a “staunch ally” to unionizing workers), two days later, Vogt and Pinnamaneni had resigned. The scandal was widely covered in the media, receiving coverage by Vulture, Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times, among others. A Google search for “Alex Goldman” reveals a “People also ask…” which contains the following questions: Will Reply All ever come back? Who were the original hosts of Reply All? What’s going on with Reply All? How much does Alex Goldman get paid for paintball? What is Alex Goldman doing now? (The penultimate question concerns a professional paintball player of the same name who, apparently, makes six figures.)

The end of Reply All became an event, or rather, what philosopher Guy Debord terms a “pseudo-event” in his essay Society of the Spectacle. As such, its staff became characters. For certain fans on social media, the story was not about a multi-million dollar media company and its alleged racism and labor violations, nor was it a story of coalition-building and unionization efforts in the face of hostility. Instead, it was the perceived personal betrayal of its hosts. Debord writes that because individuals in the Global North no longer see political and social revolutions, the “experience of separate daily life remains without language, without concept, without critical access to its own past which has been recorded nowhere. It is not communicated. It is not understood and is forgotten to the profit of the false spectacular memory of the unmemorable.”

Goldman discussed the uncomfortable reality of going from reporter to reported on and producing responses to the departure of Vogt that required him to be acutely sensitive to how his character was being received.

“People always want to know when I’m going to make a new show with my former co-host who left the show ignominiously. And our relationship was the bedrock of the show. The way we reported stories was one of us would go report it. and then come into the studio and tell it to the other one. And then one left. And we tried making the show for a year after that, and it was soul crushing and exhausting. And when he left, I didn’t have anything to say about why he left, and I still don’t. And people ask us about our relationship, and I don’t have anything to say about that publicly, and I don’t think I ever will. It’s deeply complex and there’s no good way to sum it up for angry people who want a piece of that part of me.” [Break apart] Many months after Vogt’s departure, a Reddit post appeared calling for speculation into whether or not Goldman was still married or divorced or if he was dating someone new, citing his Twitter likes as evidence of a change in his marital status. The post had at least fifty replies before it was later reported and deleted as a violation of anti-doxxing policy.

Online personalities, even those that are only loose adaptations of their source material, are treated both as characters in imagined narratives and personal friends in our own lives. Debord writes about the decrease of political potency in the neoliberal world, how a lack of agency turns into a desire to be a part of a story of progress. But neoliberalism doesn’t only reduce our capacity for political potency, it also creates a dearth of intimacy (and what Lorde describes as the erotic). Finance capital puts geographic distance between people as speculative real estate markets gentrify and remove entire communities from cities, de-unionization efforts have destroyed public transportation in the United States, and increasingly, free time is devoured by precarious contract labor and demanding bosses. These personalities, especially when they speak to us in the form of podcasts or Instagram Lives or YouTube vlogs offer a sense of friendship and company, yes, but also something more basic: the sense of knowing someone else, and, in turn, the possibility that we ourselves may one day feel known. We want to participate in something meaningful, whether it be a relationship or an event, to assert that we exist, that things happen for a reason, that we have any power over the passage of time. To interact with a face of the zeitgeist is to do something, even though we intellectually understand that their personas are curated and filtered.

All three creators spoke about navigating the difference between their internal selves and their online personas, but they also all firmly insisted on expressing a sincere gratitude for their fans and the communities of people who engage with their work. In all of my conversations—with Goldman, with Dove, with McLamb, with my friends, with myself—there is always a sheepish admission of enjoyment that comes with the positive attention of internet notoriety. It’s a rather silly thing to be self-conscious about, the simple and very human fact that being appreciated feels nice, that people come to you for your thoughts and opinions about the world. It’s a tedious balance, being sensitive and observant and wanting to share those observations with the world, and also having an internal life that gets to remain private. We say the things we do because they feel important enough to be said and we feel that the things that are important enough to be said are important enough to be heard. I ask Goldman what’s next, especially after a cease-and-desist letter from the pre-fab shed makers Tuff Shed briefly jeopardized his potential Twitch Streaming career, and he responds:

“My relationship with the Alex character is, if anything, I feel like I’m a bit of an oversharer and I should probably pull it in a bit. I think it would do me a great service to not put as much of myself into the world as I do. But also any less feels dishonest, like it would sever that connection. So I feel like I’m probably going to continue to overshare, and then regret it, and then kind of retreat within myself for a little while, and then be unable to contain my ability to overshare again, which has been the pattern.”

I see more in common between Dove and Goldman than I expected; there’s a charming mundanity in their respective creative outputs, the idea that audiences are seeing them navigating the world through their job and their social spheres, a familiarity that comes with seeing them share both the pedestrian and grandiose aspects of their lives. But unlike McLamb and Goldman, Dove’s work is a fundamentally visual pursuit, one that echoes her background as a visual artist. When I ask about her creative process, she tells me that she asks herself, “‘What is my ideal fantasy space? And how can I put pieces of it into the world?’ [To accomplish that,] I use imagery.”

As we speak, I’m struck by how shrewd Dove is, both in matters of conversation and business. She makes money through sponsorship deals, which she reveals almost fell into her lap. With her distinctive, bold style, her fans would often ask her where she found her clothes. Replying to comments became tagging brands which became receiving gifts which became a career as a paid content creator, leading her to collaborate with businesses like Revolve, Selkie, and Bellessa Boutique.

Among her business ventures is AuthenticBay, a luxury clothing and accessories sales platform that “secures the authenticity and ownership of assets by combining non-cloneable 3D fingerprint identification technology with blockchain traceability.” She co-founded the company with her father, who serves as COO and earned his doctoral degree in business in 2021. Amidst the Tweets about love and sex and iced coffee are Tweets about meeting with investors and company marketing, she adamantly expresses her active role in creating and running the business. Early branding for the company featured Dove’s friends, a diverse mix of young women, in her fantasy world: eating fruit, laughing at pastel brunches, donning meticulously coordinated outfits, and the promotional images fit perfectly in her Instagram feed, owing in part to the fact that the models were even wearing clothes from her own closet. The business seems to have changed around October 2022, when branding diverged from Dove’s production style towards a more neutral tone, but business records from the New York State Department of Corporations show no change in ownership.

Before AuthenticBay, there was the LoveDoveCompany, a candle and soap company that began with Dove creating a handful of candles to decorate her own space. Founded in 2020, her products were, truly, ahead of their time: the now-trendy bubble, knot, and figure-shaped candles sit primly perched next to handbags and fresh flowers. Swarms of comments on Dove’s Instagram requested that she make, sell, and distribute them en masse, and thus the LoveDoveCompany was born. The business’ Instagram page boasts hundreds of likes per post and multiple comments from users lamenting how fast her products sell out, the products are tagged in mood boards and by interior decorating accounts. The company closed indefinitely in March 2022. In a Tweet from September 2022, Dove wrote, “My candle business shut down when my ex smashed $2k worth of orders outside my house and I announced that everyone was eligible for a refund.”

Dove’s latest venture is designing and manufacturing her own clothing under the brand name Entinge. She’s shared photos of samples on social media, garments designed in line with the distinctive style she’s best known for: frilly and darling and Easter-egg coloured. Working with external manufacturers has proven to be a challenge, especially when trying to emphasize ethics in textile production. She hasn’t publicly listed her manufacturer, but in February of this year,she tweeted that it would require an additional $30,000 in seed capital to expand her size range to include sizes 4X-6X. She tells me, “Making something that is affordable, ethically made, sustainable, and size inclusive is so hard. It is so difficult. It costs so much money. It takes up so many resources.” But Dove is determined to release the clothing on her own terms, perfectly in line with her own vision, just as thoughtfully made as the content on her social media. It seems like her audience is drawn to Dove and all of her pursuits because she is so open about playing; her candles are props, her clothing is costume. Her audience doesn’t come to her content because they want her body or her life (though both are certainly enviable), but because they want the same sense of freedom they see in her embrace of bringing dreams and ideas into everyday life.

Days after our conversation, I find myself thinking about that small series of words: you can’t really get the entirety of a person from an image alone. We both know that by image she means photograph, and that her business ventures and the release of her public diary are, in fact, part of her image. The Dove I am speaking to is not @LoveDoveClarke, the latter is an invention by the former. @LoveDoveClarke appears in images but is also an image herself; she is someone who will never be able to capture the full complexity of Dove, but she is also someone who gets to live in this fantastical, beautiful, funny fantasy world. Dove’s success as a creator and, more specifically, as a curator, reminds me of a passage from Susan Sontag’s book-length essay Regarding The Pain of Others and her description of photography as an art:

“Ordinary language fixes the difference between handmade images like Goya’s and photographs by the convention that artists ‘make’ drawings and paintings while photographers ‘take’ photographs. But the photographic image, even to the extent that it is a trace (not a construction made out of disparate photographic traces), cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.”

I’ve hung on to those last eleven words since I first read them five years ago. I think it rings true for photography, but also so much more. Curation is the process of framing, so is definition, so is translating the abstract clouds of our feelings into words, so is trying to represent the complexity of life or even a single event into an essay or podcast episode. The artist and the influencer are both experts in framing, in knowing exactly what to leave out. To create a podcast or a song or an essay or even an Instagram post is to make a series of decisions about when, where, and what to cut. Not only is the final output of our artistic expression revealing in who we are, but so is the process of editing and curating — there is no easier way to learn who you are than by deciding who you don’t want to be. McLamb speaks about this phenomenon as she writes her upcoming album, “Songwriting is the perfect defense mechanism, because you’re like coming up with a central motif, you’re building it out, and you have so few words to do it with. So you have to be extremely perfect with all of it. I really think this album is going to surprise people, that it’s almost like a character of myself that they don’t know. And I’m wondering how this is gonna be perceived. And of course, the whole thing is very highly edited, but it’s a perfect medium for figuring out stuff within yourself, because we all have these competing parts of ourselves that if we lean into, that characterization actually reveals a lot about how we interact with ourselves.”

People come to social media to find figures that are both aspirational and “authentic,” whatever that may mean. Audiences feel shocked and betrayed when creators cannot be what they want them to be, either when they feel a creator’s persona is too detached from their offline self or when a creator seeks to set up boundaries with their audience. But what is “nonfiction”? Excluding anything from a story is a choice, even when it is an unconscious choice, and we cannot represent the full and total context of any person or narrative without editing some things out. The process of existing online for an audience is a fundamentally curatorial, and therefore artistic, exercise. Of course, it is not only artistic but also economic; once the Self has been created, it must be performed. Dove remarks that both positive and negative reception to her character is the result of audiences feeling like they know her well enough to respond to the person they think she is. She notes that the people who love her and the people who hate her both “spend enough time on the internet watching my page that they have come up with a version of me in their head,” whether as friend or villain, then goes on to say that being reliant on her audience means she often must censor herself in ways she wouldn’t otherwise. Goldman brought up an anecdote about his former colleague, audio producer Kaitlin Roberts, how she would produce and edit her own voice and always refer to that voice as “the Kaitlin character.” When Goldman said, “but it’s you,” she responded, “It’s not me. It’s me conscious that there is a microphone in front of me.”

All three creators I spoke to mentioned that having a sizable online platform means they must monitor the things they say to a degree that isn’t required in day-to-day life. All three of them were also quick to mention that they don’t think this is some output of “cancel culture” or a wholly evil institution, in fact, it makes them more thoughtful and considerate. McLamb has no desire to soften her political beliefs to grow her audience, she wants to challenge them to think differently and disagree with her in a productive, informed manner. Still, there exists an energy to act, to participate in an event, and allowing oneself to be upset over a betrayal from an internet figure satiates our desire to do something. McLamb tells me, “I think we’re living in a crazy historical moment where so much is happening and there’s so much to be angry about and to talk about, and yet all of us feel massively disempowered to actually have any real change towards that end. So I think people’s energy just gets frenetic in their own bodies, and then they’re constantly looking for a way to release, release, release, release. And a very safe place to do that is on a person that you don’t know, who has a bigger platform than you, and who’s just this representation of the things in your mind that you’re angry about.”

McLamb’s comment reminds me of a passage from an interview with anthropologist media theorist Edmund S. Carpenter in a 1970 issue of Playboy. Carpenter, a colleague of The Medium is the Message author Marshall MacLuhan, describes the possibilities of digital communication,

“Today’s invisibles demand visible membership in a society that has hitherto ignored them. They want to participate in society from the inside and they want that society to be reconstituted to allow membership for all. Above all, they want to be acknowledged publicly, on their own terms. Electronic media make possible this reconstitution of society.

But this also leads to a corresponding loss of identity among those whose identity was defined by the old society. This upheaval generates great pain and identity loss. As man is tribally metamorphosed by electronic media, people scurry around frantically in search of their former identities and, in the process, they unleash tremendous violence.”

There seems to be this belief, usually recited condescendingly by Baby Boomers and newspaper opinion sections, that the reason we’re all so miserable is that we believe everything we see on social media is true and real. I think this is — pardon my language — profoundly silly. Certainly, we love to see the beautiful and rich lifestyles of the beautiful and rich, but more so we love that they perform for us. It is our tastes and politics they must consider before they speak, our desires which they must confront before building their own persona. Politically and economically neutralized, we can believe we hold some power over these public figures by, in a tangible, economic sense, being their boss. Karl Marx writes about this phenomenon in his 1844 essay, “Estranged Labour,” how “The object of labour is, therefore, the objectification of man’s species-life: for he duplicates himself not only, as in consciousness, intellectually, but also actively, in reality, and therefore he sees himself in a world that he has created.”

This desire to consume a person as a commodity and the desire to see oneself as a commodity is reflected in our desire to implicate individuals in events, the same friction Carpenter described fifty years ago in Playboy. It’s an assertion of control, one that allows us to believe we have control over others and control over the narratives of our own life. It feels like there is a pre-set life cycle we can’t help but participate in: creators must develop personas for personal safety and to market themselves online, audiences then develop relationships with these personas to make up for the lack of community and intimacy in our fragmented, neoliberal geography, our relationship with those personas (both when they are succeeding and when they are failing) becomes what philosopher Guy Debord would describe as a “pseudo-event, lost in the inflation of their hurried replacement at every throb of the spectacular machinery.”

But maybe this relationship between the audience and content creator begins long before we even power on our phones or computers. It would be foolish to try and assert that there is some sort of “true” self that is distinctly different or better than the curated persona, or to say that the online persona is different than the general social personas we inhabit when in front of others. There is no clean distinction between “the internet” and “real life;” the realities of the internet have plenty of intersections with our material, physical world. Perhaps our complex relationship with the online personas of influencers stems from the fact that they allow us to believe we are somehow realer or truer than they are. We all have a persona. Well, no, that’s not quite right. We all have dozens of micropersonas, the version of ourselves we play at the office or in the classroom or at the bar or the family reunion. We have a persona we play for ourselves, in private, when we want to indulge our own internal voyeur. In observing others, we get to believe that we are uniquely complex and multifaceted, usually in some sort of “deep down” way, because it is deeply uncomfortable to realize that we exist in some defined way in others’ imaginations. Perhaps it is the embrace of the individual as unknowably rich and complex that will remove us from individualism and towards a more holistic understanding of our artists, our communities, and ourselves.