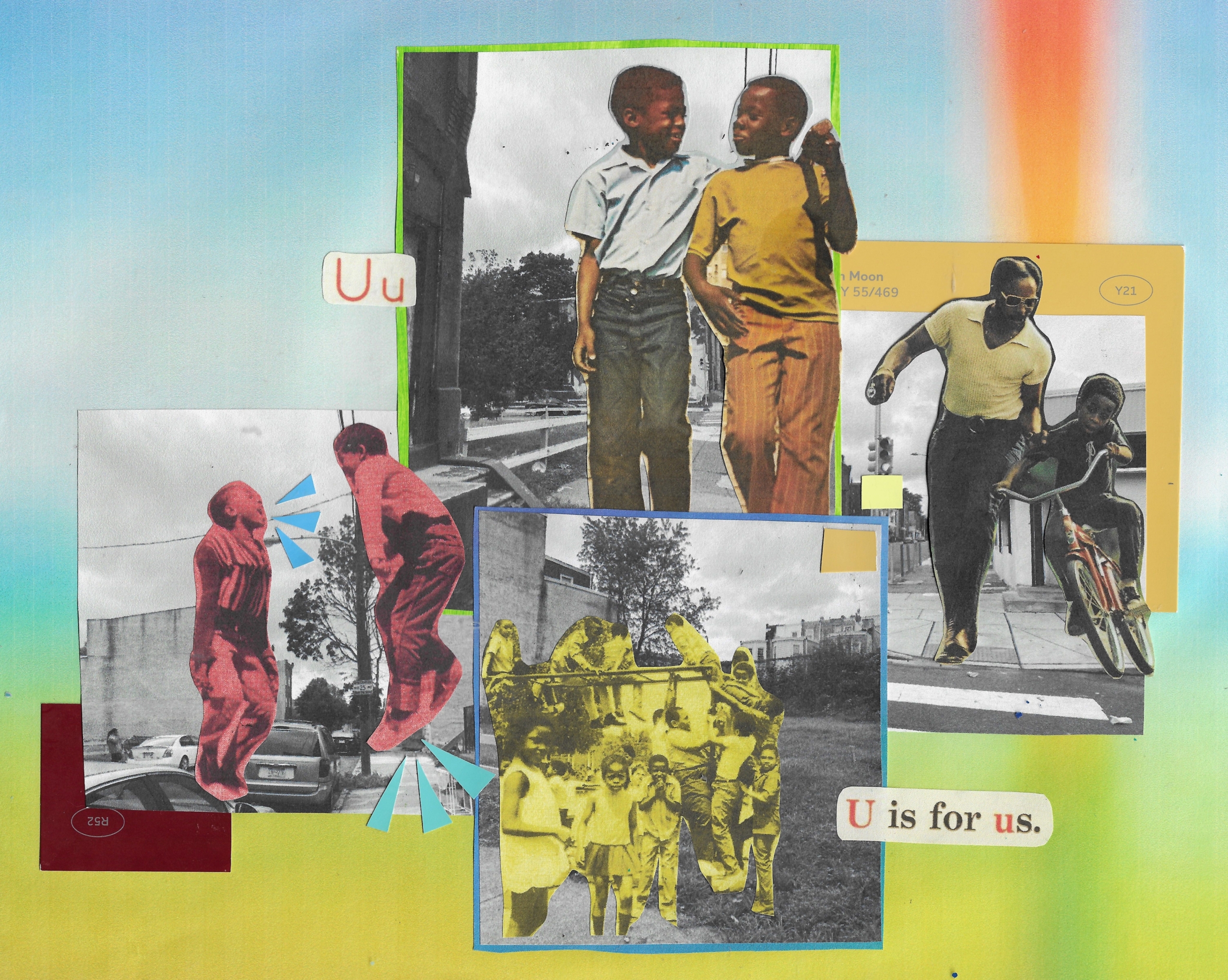

Art by Tina Tona

Story by Maya Jenkins

In late July, I moved to Philadelphia to live with my best friend after going six months without seeing him. Along with my belongings, I carried the hopes that I might dust off whatever semblance of independence I had left and reclaim my young adulthood in a new place. I was excited. Elated, really. I also knew that my endeavor necessarily imported risk into the city I was to become a short-term resident of. As a stranger taking up space at a time when the air feels all the more sacred I, of course, sought to limit opportunities for the spread of the coronavirus. But that isn’t the risk I’m referring to. From the moment I began my housing search, I was painfully aware of how easy it would be for me to participate in the gentrification of a Philadelphia neighborhood.

As a young Black woman who has consistently participated in racial justice work, the idea that I might become an agent of what some call a modern extension of colonialism—gentrification—felt anathema to me. But it wasn’t. I am a young, healthy, college-educated woman with disposable income. I am the target audience of those peddling luxury units in “up and coming neighborhoods.” As I combed through apartment after apartment, searching for a pathway towards exercising my own independence, I realized that many of those pathways cut straight through the heart of Black communities.

At a more basic level, the very notion of my independence was fraught. Where had it come from? What had enabled it? Was it the fact that my parents could afford to front the rental bill while I made spaced-out payments to them? Or was it the fruitful professional network I had been able to cultivate while attending Harvard University? Perhaps I could even trace its origins back to before my birth—to decisions made by my mother or by her father before her. The urge to reflect upon the privileges I have been steeped in became heightened as I got closer to my move-in date. While I was to become a transient visitor to the city, with no intention of remaining for longer than two months, I was to become a visitor with roots that run through the city’s northeastern streets.

The story of my being is set, in part, in Philadelphia. My grandma was born and raised in Philly; she grew up poor, the daughter of Bahamian immigrants. She has lived a life radically different than my own and at times, it shows. When I told my grandma that I was moving to Philadelphia, she said, “you won’t make it.” Her humor, as always, was biting and doubled as truthful commentary. Could I possibly endure the life that she has known? The answer, if it exists, is of little consequence. I may currently live in the city of her birth, but I will never know the life that she knew here.

My grandma, Olga Culmer Jenkins, is a beloved matriarch in my family. Her mother, Letina Culmer née Bethel and father, Leopold Culmer, came through Ellis Island from The Bahamas and settled in Philadelphia in 1919. By my own father’s description, my grandma’s father was a professional photographer (but my dad’s cousin describes him as a “sometimes” photographer). My grandma’s mother was a domestic worker who mostly took care of children. My grandma and her sister, my Great-Aunt Eloise, grew up in North Philadelphia, in a neighborhood that Aunt Eloise called ‘Depressed Area #1.’ A quick online search unsurprisingly reveals that “one of the most profound [reasons for North Philadelphia’s ‘urban decay’] can be traced back to an 80-year-old social engineering effort, when the federal government exacerbated racial wealth disparities and housing segregation across the United States.” Redlining and other racist practices were used to create segregated neighborhoods in cities across the country and my grandma’s neighborhood was one of them.

“The Black people all lived together,” my dad’s cousin told me. The Black doctor lived on one corner, the Black lawyer lived on another. There were the cousins—Austin, Gerald, David and Alan—who all lived nearby. There was the haberdashery that my grandma’s uncle owned. There was the Sunday School (my grandma would pronounce it ‘Sundee’) at the local Anglican Church where the two young sisters taught. An effusive sense of togetherness, of Black togetherness, shapes these descriptions of my grandma’s childhood. As someone from a largely wealthy, predominantly white (though diverse) suburb, this sense of Black togetherness is a quality that I don’t think I have ever experienced, but one that I am jealous of. Her neighborhood block, saturated in Black beauty, Black power, Blackness, helps to explain my grandma’s staunch Black Nationalism, the afro she has sported for at least 60 years and her disdain for my ‘straighter’ stylistic choices (which I have recently sworn off). I would be remiss if I didn’t admit that in reflecting upon my grandma’s Blackness I often begin to feel as though my own Blackness has been watered down, tainted by a self-contempt conditioned by white supremacy. But that is the last thing that my grandma would want me to feel. Her Blackness is my Blackness. Her life gives life to me. Her story is a part of mine and if I hold it close, it will guide me.

My grandma was part of a Black North Philly community and she invested in that community, even when it, like all communities, was imperfect. There were many times during her childhood that my grandma’s home could no longer support her and her sister. Sometimes, people in her family harmed one another. When that happened, she and her sister were placed into foster care until they were eventually brought back home. Other times, my grandma transformed her home into a place of refuge for others. Upon her arrival at Temple University as an undergraduate, my grandma quickly became best friends with a woman named Lee. Lee’s presence in my life has always been symbolized by the small Black doll she gifted me when I was a child. The doll is named Baby Lee. Just a few years before they met, Lee’s family had been interred in a Japanese internment camp in Washington state. They were among the roughly 117,000 people who were directly impacted by Executive Order 9066, which mandated the “relocation of Americans of Japanese ancestry” to militarized zones in California, Oregon and Washington. Lee did not have a home to return to during those years, so my grandma asked her father if Lee could live with them in North Philly. Her father said yes.

I feel like a flâneur in this city—a wanderer content to take up space and take in the sights while “working from home.” But for my grandma, being at home in Philadelphia meant that she had a responsibility to work towards realizing a more just city. Knowing my grandma, I can only imagine that she protested and organized as a young woman. Later, she would participate in the Civil Rights Movement, organize domestic workers and help to desegregate the public schools that my dad eventually attended. I do know that as students at Temple, she and my Great-Aunt Eloise volunteered at the Red Cross collecting blood donations until they learned that the Red Cross separated the blood they collected from white people from the blood they collected from Black people. This was, of course, a racist policy that perpetuated the idea that Black people were somehow biologically distinct from and inferior to white people. The sisters immediately organized and pushed the Red Cross to reverse the policy, which they did. There is so much beauty and grace and pride and power in the way that my grandma has lived her life. That life began here. In Philadelphia. On North 19th Street between West Susquehanna and West Dauphin.

I was sitting inside my apartment, staring out of my floor-to-ceiling windows at a gray Philadelphia day when the urge to visit my grandma’s old home grabbed hold of my chest. Although I am prone to inertia, I felt as though I would not be able to sit still until I was standing in the middle of her block, taking in the sight of her childhood home. My family visited the house with my grandmother a few years back, but my memories of that trip were hazy—those of a child who could not quite grasp the value of the moment. I wanted to feel the emotional weight of the space and the lightness of it too. So I secured my mask and headed to the address my dad’s cousin had given me. During the ride, I watched as the physical world transformed, block by block. The lush, tree-lined streets and boutique shops and white people surrounding my apartment gave way to encampments of unhoused people and soon-to-be finished, glassy apartment buildings wedged between corner stores and Caribbean restaurants—telltale signs of gentrification. As I approached the end of the trip, those landmarks too gave way to boarded up storefronts, vacant lots and “Thank You For Not Loitering” signs. And then I was there.

I thanked the driver, hopped out of the car and stood in the middle of the street. The laughs and gleeful cheers of small children echoed around me as I glanced down at my maps app, up at the building numbers and back down. Having trouble finding my grandma’s building, I began pacing the block, passing the same gleeful little Black girls over and over. It was not until I was standing in the same exact spot as my Maps pin that I realized—my grandmother’s home was no longer there. A grassy, empty lot, littered with trash sat in its place. The condemned red-brick building that my family and I visited years ago was gone. The house that my grandma started her life in, that she and her sister played with their cousins in, that Lee found as a second home in, was gone. Before I left, I had expected to feel the weight of my privileges or, rather, the weightlessness they afforded me, sitting inside of me. Instead I felt nothing. I had expected to feel the way I felt when my grandma belittled my family and I for fitting right in with the bougie Black Martha’s Vineyard crowd during one family vacation, or when she refused to go with me to the Whole Foods Market that had just opened across the street from her Upper West Side apartment, or when she judged my sister and I for refusing to join her in eating recently expired food. I felt none of these feelings. Only emptiness. I continued to walk around aimlessly, peering around street corners to find other dilapidated houses and other vacant lots. And I wondered, whose lives had unfolded here? Whose lineages ran through these blades of grass, these cracks in the concrete?

It was only as I began my journey out of the neighborhood that I began to feel something. It was not whatever mild form of guilt that the children of so-called class-migrants, people like me, might feel upon recognizing the wedge that their socioeconomic status drives between them and their elders. It was rage. The physical transformation of the landscape as one enters, or re-enters, a neighborhood white people live is staggering. Trees where before there were none. Vacant lots? They barely exist. Boarded up homes? Nearly unheard of. There certainly were none as I got closer to the Philadelphia Art Museum. What I saw confirmed (as if I needed confirmation) that hatred for Black people is built into the lived environment—it is in the air, in the soil, built and rebuilt intentionally, brick by brick, even as brick and mortar homes like my grandma’s are foreclosed upon and then torn down. There are moments in the lives of Black people when we feel as though we can read our surroundings and receive from them a message of loathing. The language of racial oppression lives in images and environments and texts. And while I know that histories of segregation, redlining, wealth disparities, inequitable school systems, a racist criminal justice system and slavery all led to the dramatic shift in landscapes that I saw on my way back from my grandma’s neighborhood, I didn’t think of those histories. I read the hatred. And then I felt it.

I have no delusions about my family’s story. I offer no fantasy touting three generations of Jenkins family members as symbols of an imagined American Dream. I am deeply aware of my proximity to, if not my participation in, institutions that oppress Black people—institutions in which I too am devalued and degraded. Our story is unfolding as one that demands the maintenance of memory, self-reflection and a robust discussion of responsibility—both personal and collective. Before moving to Philadelphia, I had a version of that discussion with myself, with my parents and with my soon-to-be roommate that was narrowly tailored to the move. Out of those discussions came a few specific, but by no means all-encompassing or perfect, actions that I took. First, I rejected every single apartment listing that used a version of the phrase “up and coming neighborhood” in its description. We did research on which neighborhoods were being gentrified and crossed them off of our list. I will be the first to note that not everyone can do something like that, but because we could, we required ourselves to. We settled on a short-term apartment in the heart of Old City, a neighborhood considered to be “non gentrifiable” due to its historically upper and upper-middle class makeup. Months before I moved, I followed several Philly-based racial justice organizations on Instagram and began to make recurring donations to the Philly Bail Fund. I also reached out to folks I know from Philadelphia to learn more about racial justice and organizing work happening in the city and how I could support it. While developing a strong focus on individual responsibility in the context of systemic—and sometimes global—forms of oppression is often used as a tool to maintain a capitalistic status quo, we can and must be intentional about how we enter new spaces and how we show up for one another once there. This is especially the case during the confluence of three crises—racism, economic collapse and public health—each one of which exacerbates the others.

It has been months and months since I’ve wrapped myself in my grandma’s arms. I don’t know when I will see her next, or if I will ever be able to touch her again. But I want her to know that, on countless occasions, she has guided me towards a way of living that honors my family and the collective history of Black struggle. She has guided me towards a more honest, generous and thoughtful self. I love her. Ultimately, it is that love that must fuel my independence just as it grounds me in my responsibility to the city that has welcomed me and to Black people to whom I owe everything.