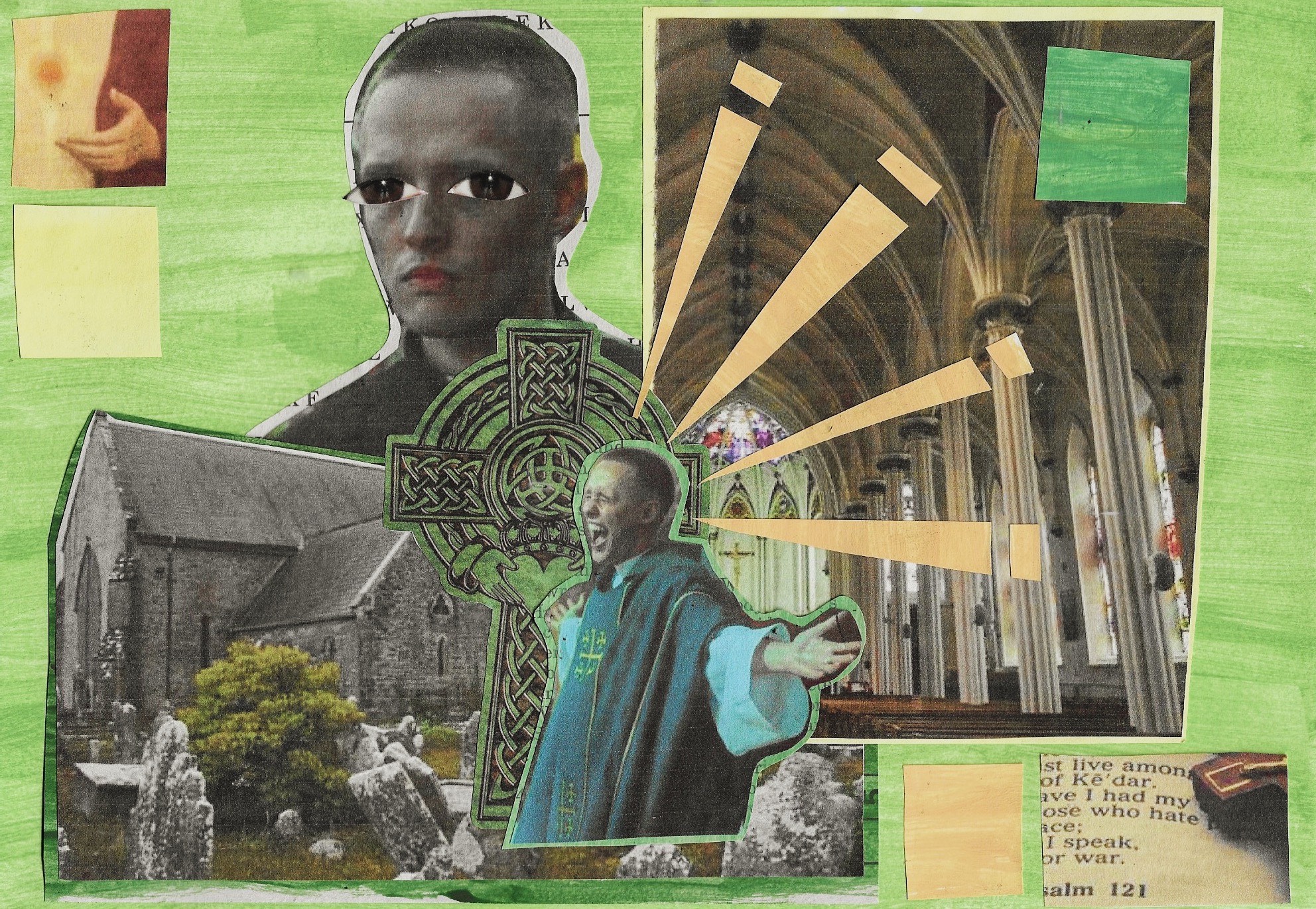

Art by Tina Tona

Story by Remi Riordan

St. Augustine of Hippo, a Catholic theologian and philosopher, once said, “If there was no good in what is evil, then the evil simply could not be.”

This statement on the dichotomy that is good and evil, on how no man is purely evil, felt incredibly truthful and relevant to Jan Komasa’s “Corpus Christi,” a Polish film about a young man who, after being released from juvie, pretends to be a priest.

As a priest, Daniel is good, even with evil in his past.

His goal was never to con the townspeople, but to help: raising money for a family’s medical treatment, helping townspeople grieve their children’s deaths, attending local events.

Daniel was never allowed to join a seminary because of his violent crimes, but arguably that was beneficial to him—he spoke from the heart, gave straightforward practical advice in confessionals, and did not seem caught up with what the Catholic Church would deem acceptable.

Throughout the film, we see Daniel slowly grow more comfortable with scripture and his role as a priest within the town. What had started as an off-handed lie to Eliza (Eliza Rycembel), a young woman, to prove a point, had become not only his life, but a reason for him to continue living.

In many ways, Daniel became the priest he was impersonating. In one of his first masses, he states, “Silence can also be a prayer,” and while his ad-libbed sermon was meant more to deflect his ignorance of scripture, later he seemed to have taken that practice to heart while sitting with an old woman on her deathbed—sitting in silence, holding hands, as a way to bring her peace.

Still, this did not mean Daniel felt any less conflicted—maybe he was even asking himself the very question I had—Why is seminary necessary to give people hope and solace?

The film is filled with moral and philosophical questions, yet it rarely gives any answers. It feels purposeful in this way so audiences, just like Daniel, question the decisions and the subsequent brutal and visceral outcomes.

More than just the thoughtful and precise writing by Mateusz Pacewicz, the cinematography is beautiful and its subdued lighting works to illustrate Daniel’s moral quandaries. He is frequently shown alone, at night with soft colored lighting, sometimes reading the Bible or praying with rosaries.

The performances throughout the film feel honest and without judgement of the characters they’re portraying. Bielenia’s stunning performance as Daniel is intense and joyful and sad—every emotion he portrays feels real and raw. When he preaches or cries or laughs it seems so natural to Daniel because of the realism of Bielenia’s acting.

In so many of these moments, the audience feels sympathy for Daniel and his lies, wishing he had been allowed to enter a seminary; wishing we could forget about his past and move forward. He’s shown to be so passionate and seems to truly care about giving people hope and solace—so why can’t we just forget?

But Komasa doesn’t want you to forget who Daniel was before imitating a priest. He doesn’t want audiences to see Daniel as only good.

He reminds us of this when Daniel gets into a violent fight with young men from the town. He reminds us when Daniel breaks his sobriety with not only liquor, but cocaine. He wants us to see Daniel trying to change—to not be the person he was—but not always succeeding.

Komasa doesn’t want us to forget, rather he wants us to forgive—because as Daniel would say, “Forgiveness is love.”

Rent now online: At The Museum of The Moving Image or Guild Cinema