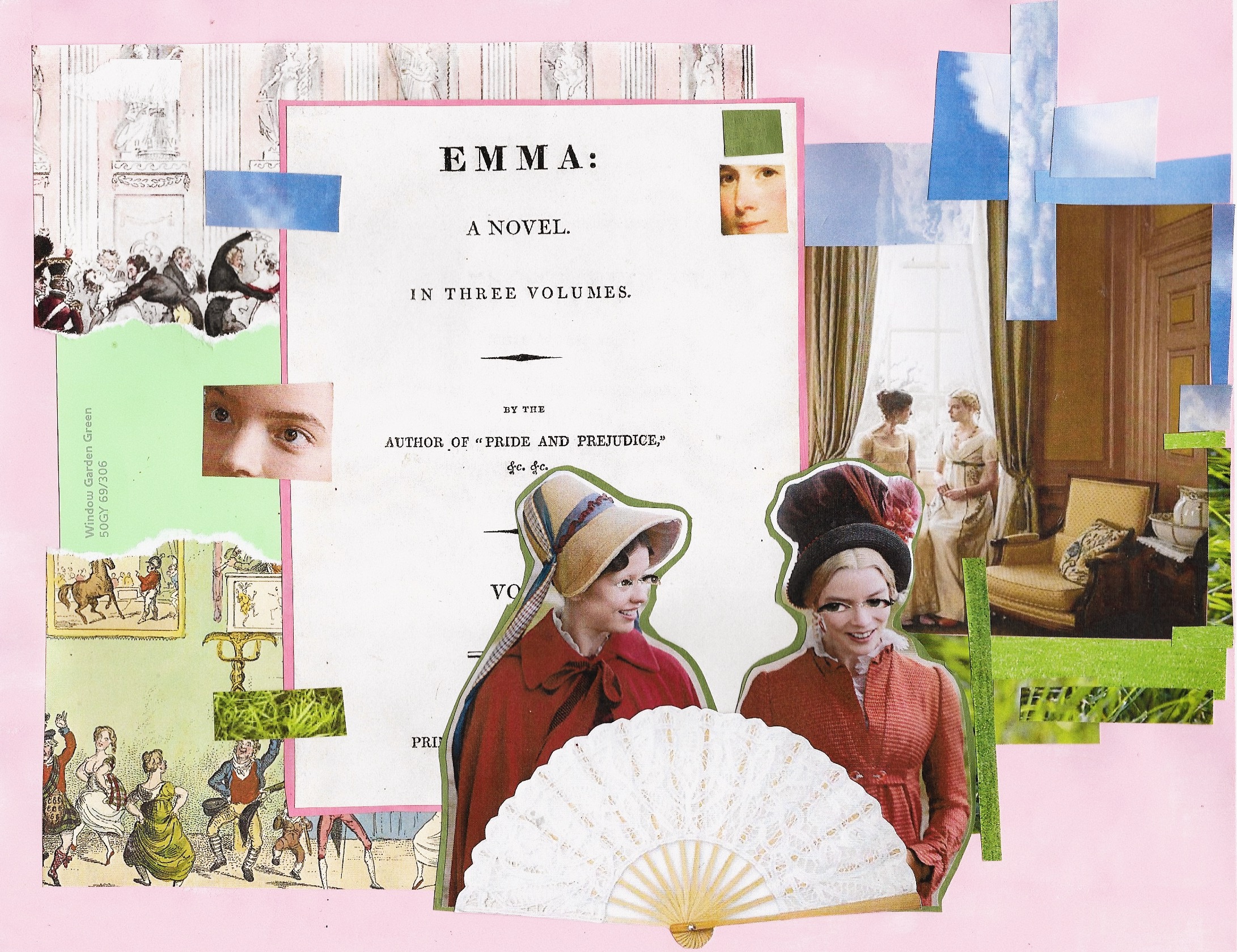

Art by Tina Tona

Story by Remi Riordan

“I only want to keep Harriet for myself,” Emma tells Mr. Knightley. Emma is no longer interested in matchmaking, especially for her closest friend Harriet.

Emma Woodhouse (Anya Taylor-Joy) is a “handsome, clever, and rich” 21 year old. She’s, in a sense, homebound due to her hypochondriac father who she cares for dearly and staunchly states that she has no interest in marriage, instead spending much of her time finding love for others.

Harriet Smith (Mia Goth) is a kind and naive 17 year old. Mr. Knightley (Johnny Flynn) at one point worries that she “knows nothing of herself and looks to Emma for everything.” She is poor and unsure of whether or not her father is a “gentleman”—making it harder to find her a wealthy suitor.

Jane Austen’s “Emma” is a story audiences have been introduced to many times before. Now in Autumn de Wilde’s directorial debut entitled “Emma.”, de Wilde presents the young women as more than mentor and protégé, but dear friends.

In this moment between Emma and Mr. Knightley, a close friend she has known for many years, she is no longer interested in such set-ups. And while Emma is being selfish, she’s also being honest. She lost her mother at a young age and Mrs. Weston (Gemma Whelan), her governess for many years, has recently married and while only moving half a mile away, it is still a much greater distance than down the hall.

Simply, Emma loves Harriet and has no interest in losing her. Emma, a young woman who has little interest in matchmaking for herself, has found her companion a different way.

“Emma.” is a love story and truly there are many weaved into the plot, yet the most consistent and forgiving and intimate is the one between Emma and Harriet.

There is a scene in which Emma and Harriet dance in Emma’s bedroom. They have their hair in tiny white bows—to keep their little curls in tact. No longer dressed in their almost angelic dresses, they’re in nightgowns and exposed corsets. They twirl and Emma helps Harriet to learn the dance for the ball Mr. Churchill (Callum Turner), a possible suitor, is hosting.

And then they hug. An intimate and caring hug. It is one of the most timeless scenes throughout the film; audiences are watching these young women in something so universal as a sleepover. It is one of the few scenes where they are stripped of their fancy empire dresses and reserved words.

De Wilde’s adaptation is wonderful. It is fun and sweet and often feels like watching thousands of beautifully staged paintings perfectly woven together—not surprising as de Wilde is an accomplished portrait photographer. We get the sense, especially in the wide shots, that there is a certain pause before the action begins. Like when Emma and her father, Mr. Woodhouse (Bill Nighy) sit to eat or when Emma and Harriet, wearing delicate white dresses, run down the green grassy staircase.

The lighting, costuming (by Alexandra Byrne) and hair styles are all important to the story as it gives us a look into socio-economic class differences. When Jane Fairfax (Amber Anderson), another young woman, does her own hair, simply parted in the middle and pinned up—without the intricate small curls—snarky comments are made. And while Jane’s aunt, Miss Bates’ (Miranda Hart) home above a shop is dark and small, the wealthier characters live in grand estates where they host lavish dinners and have servants that do tasks as minuscule as blocking a cold draft.

Many of the characters who at first seem to be there for comic relief, like Miss Bates and Mr. Woodhouse, later reveal deep insecurities and struggles. Mr. Woodhouse’s seemingly silly comment calling his older daughter’s wedding a “terrible day” is because of his fear of abandonment—and likely the very reason Emma claims she has no interest in marriage. Miss Bates is frequently shown to be an annoyance to Emma, and at an crucial moment, is seen humiliated and quietly crying.

In that moment, Emma reveals a crueler, unfeeling side of herself, and thankfully she is embarrassed and ashamed. It sparks many moments of reflection: of her coarse words about Jane and her selfishness to Harriet.

So while “Emma.” is a love story, it is also a coming of age story. It is a story about a young woman growing and learning humility. A story about a young woman who has felt homebound because of her father. A story about companionship, whether that be familial or romantic or platonic.

A story, that despite ending with romantic love, still feels as if it’s making the argument that Emma and Harriet’s friendship is the most important love story because they grow together and forgive each other and laugh with one another. Their story is layered and complex and at times all consuming.

In the end, Emma falls in love with a man, because of course she must—this story was written in the early 1800s. But she also falls for a man who is smart and challenges her because despite her being referred to as vain throughout the film, she always aspires to more than beauty.

Early on in “Emma,” while complaining about the young women’s friendship, Mr. Knightley states, “I’d like to see Emma in love.” And luckily for us, we see that twice.