Story by Remi Riordan

Art by Tina Tona

“How does that make you better than a terrorist?” A television commentator, seemingly a left-wing secular Israeli man, asks a row of men discussing the mass-murder of 29 Palestinian Muslim worshippers by religious-extremist Baruch Goldstein.

To answer his question, it doesn’t.

But to Yigal Amir (played by Yehuda Nahari Halevi), Goldstein is a martyr, someone doing God’s work, while the Palestinian suicide bombers who attack Israelis are terrorists. To him, it is a question of religion and land and ownership, not violence.

In the film “Incitement,” director Yaron Zilberman takes a look at the true story of the years leading up to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination and the radicalization of young university students including Rabin’s assassin, Yigal Amir.

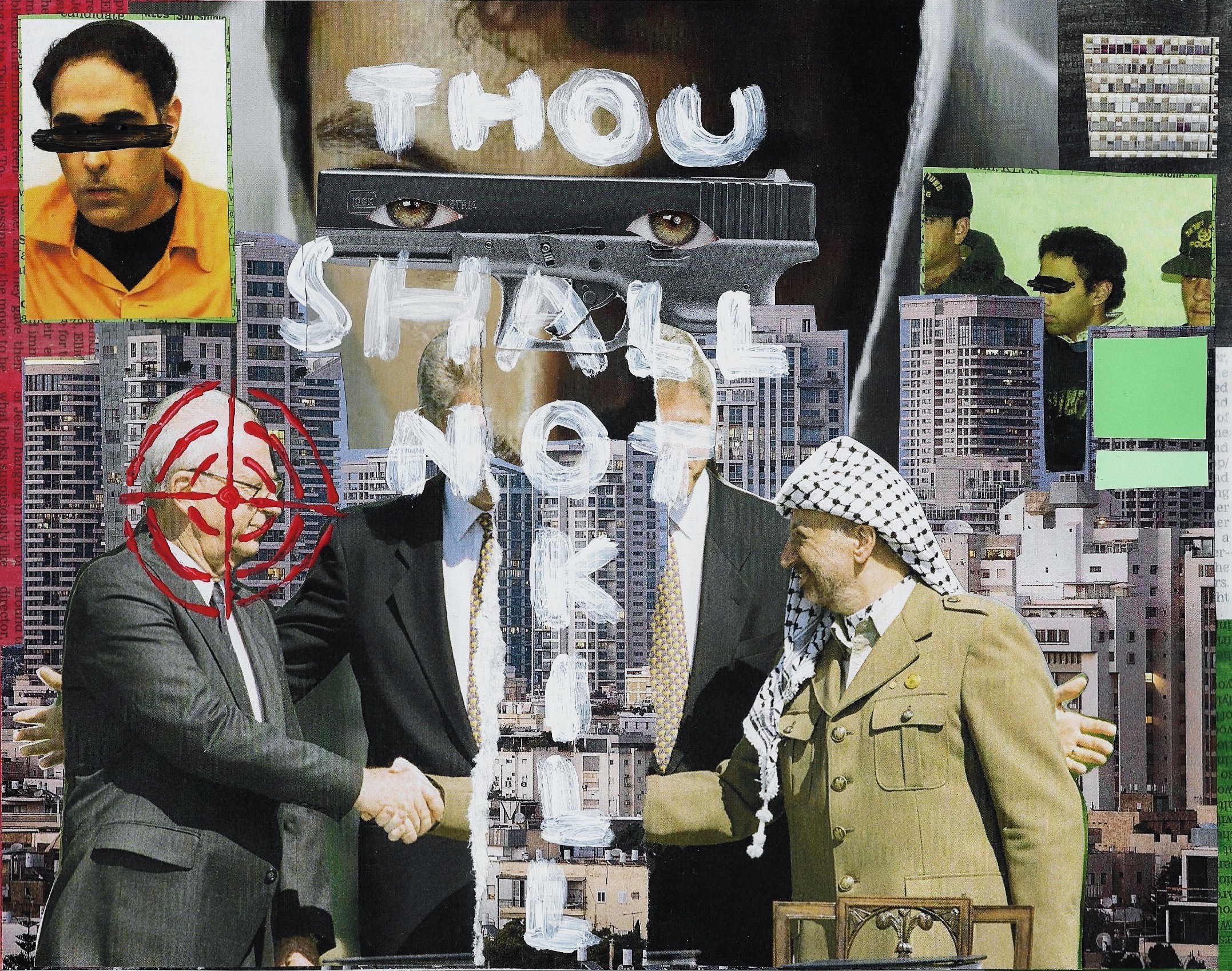

The film opens up to a radio broadcast of Rabin speaking at the White House in Washington D.C. with Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and U.S. president Bill Clinton. Both Rabin and Arafat are there to announce the Oslo I Accord, and it feels hopeful. They speak of peace, a chance for both nations to live next to one another without violence.

But quickly the film informs the audience that the young man, Yigal, listening to the broadcast is not happy with the news and neither are many other Israelis.

In fact, this is the beginning of a long clash between not only Israelis and Palestinians, but secularism and ultra-orthodox Judaism—on whether or not Israel should be run with democratic law or Jewish law.

This conflict is seen throughout the film: when Yigal’s father Shlomo (played by Amitay Yaish Ben Ousilio) tells Yigal that his head is filled with lies or when he asks his girlfriend Nava (played by Daniella Kertesz) if she would want to marry a martyr or when he calls a secular young woman a slut for wearing a low-cut top.

They hear Yigal’s words—his staunch arguments for nationalism, his dangerous interpretations of the Torah—and are afraid of him and his ideas.

And while many are afraid of his ideas, many agree with them as well. Large protests and rallies are held against Rabin and the Oslo Accords. Rabbis regularly label Rabin as an “informer” a reference to a Torah passage that justifies the killing of such a person for hurting the Jewish people. And many of Yigal’s friends hold nationalist views.

The people Yigal listens to and surround himself with confirm and validate his ideas. They aid him in his plans to form a militia, which later turn into plans for assassination.

And that is what makes the rabbis such an interesting aspect of the narrative. They regularly preach in favor of the murder of Rabin, yet when asked explicitly, they leave Yigal to his own interpretation—allowing him to decide how seriously he should take their holy words.

Yigal decides to take their words as a call to action. He decides he will, like Goldstein, become a martyr.

But his relationship with his mother Geula (played by Anat Ravnitzki) seems to be unaffected by his political and religious radicalization. While his father can see him becoming more and more radical, his mother seems to ignore it or just plainly not recognize it. She sees him as innocent and a victim to his failures, not the cause of them.

Zilberman presents Yigal as a complicated figure. He, of course, is first a murderer, a violent man—someone who was said to have taken pleasure out of beating up Palestinians while in the military. But he was also a law and computer science student and had a normal and loving family. Zilberman understands the importance of presenting both.

That radicalization is not something that happens in isolation. That these ideas can permeate in spite of a good education and a healthy home life, not always because of them.

Towards the end of the film, when the time has finally come and all the preparation and trials have been completed, Yigal stands at home in front of a dark red velvet parochet, a Torah ark covering, embroidered with Hebrew.

He kisses it and prays to it and we see a glimpse of the gentleness Yigal’s father once spoke of. But we also see Yigal as a hypocrite and Zilberman makes sure that we see him as such.

When he prays to the parochet, there is a subtitle on the screen and it is not for spoken language. The Ten Commandments are embroidered onto the dark red velvet. Ten important religious laws, yet only one is displayed on screen. It reads, “Thou Shall Not Kill.”