Story by Remi Riordan

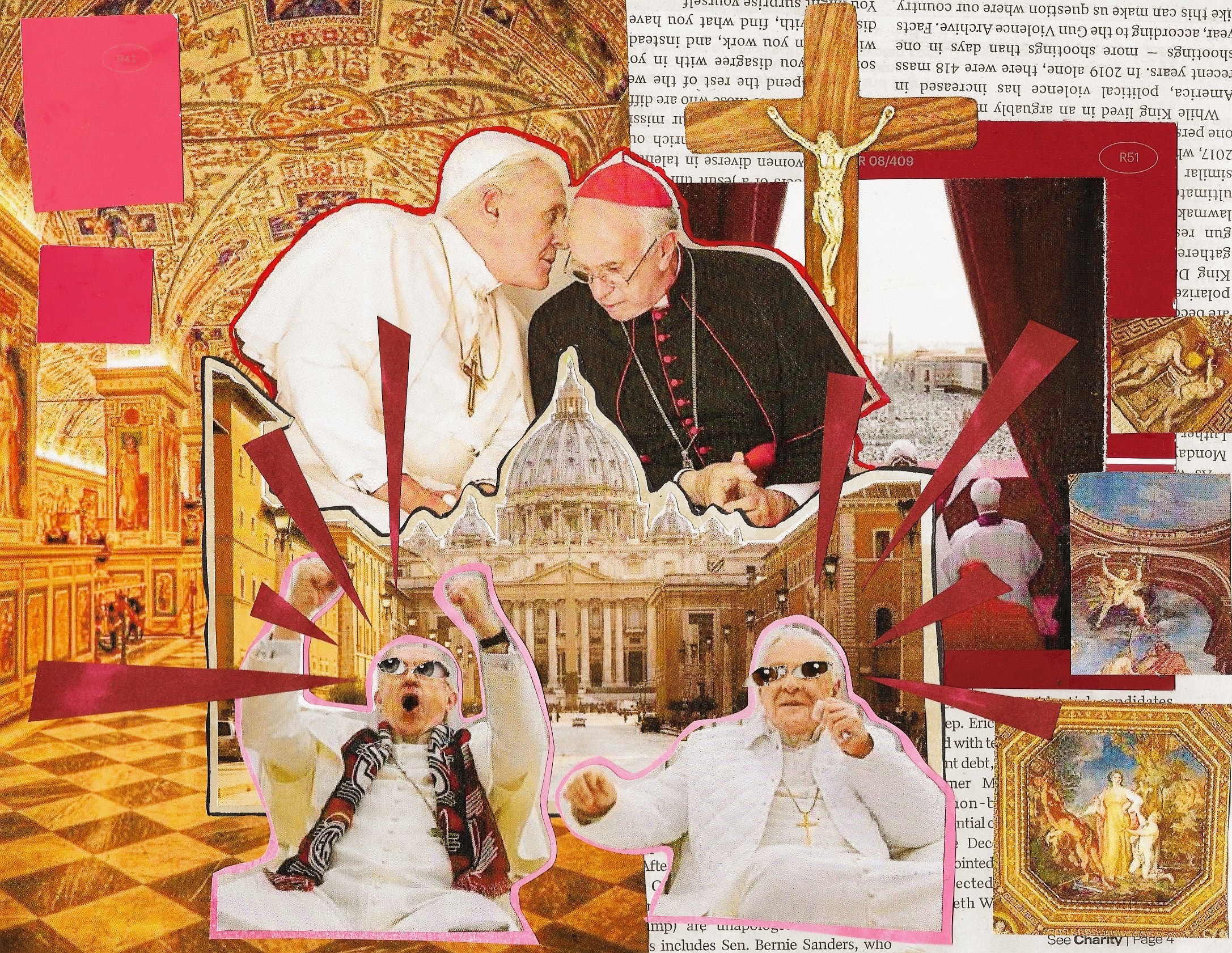

Art by Tina Tona

Compromise and change. Tradition and reform. Being alone and being lonely. There are many simple, yet powerful dichotomies that Netflix’s “Two Popes” manages to weave into its two hour running time. Yet, the difference between compromise and change seems to be the overriding question the film seeks to answer.

“Two Popes” is, at its core, a film about two men within the Catholic Church who, despite their vastly different ideologies, become friends and change each other for the better.

From the start, the director, Fernando Meirelles (“City of God,” “The Constant Gardener”), informs the audience of the main conflict between the two—the desire to stick to the conservative traditions of the church versus reforming the church to make it more open and merciful. The way Meirelles first chooses to illustrate this conflict is not only subtle, but powerful—he chooses music.

As the film progresses it is clear that the two popes’ knowledge and understanding of music informs their understanding of the world. Jorge Bergoglio (Pope Francis), played by Jonathan Pryce, is seen in the bathroom humming Dancing Queen by ABBA—an iconic song, one that is instantly recognizable, while Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict), played by Anthony Hopkins, does not know the song.

The pop track is then played while the cardinals walk to cast their votes for the next pope—a clear reference to what the cardinals are really voting on—whether to stick to the traditional conservative ways of the Catholic Church, or to vote for a more progressive and lenient future.

In this scene, the cardinals vote for compromise, or as one newscaster calls it, “unity,” within the church. But this choice, a choice not for change, but for the status quo, marks the true beginning of the film, where the two men come together to figure out not only their own personal distinction between compromise and change, but their humanness.

More than their understanding of music and catholicism, the two men struggle to find commonalities in many aspects of their life. While Francis chooses to engage with his communities—speaking to masses, feeding the hungry, and living amongst the people, Benedict isolates himself—eating alone, rarely interacting with the public, and living in luxury.

Despite these differences, they have the connection of God. They hear him and speak to him. And while Benedict isolated himself and later realizes he never really experienced the world he was meant to serve, he said he always felt God at his side and never really felt lonely until recently.

As a film steeped in history, both of these popes’ personal histories and the scandals of the Catholic Church, Meirelles chooses to weave in footage, both real and fake, constantly confusing reality with fiction. At times, it is unclear what is real footage of the actual events or staged—only when the popes are on screen is it truly clear.

But this feels intentional, to have the audience feel as if they are watching a documentary—showing blurry images, television broadcast reports, and footage of the many borders and walls throughout the world. Even in the way it is filmed, it feels personal, like the audience is watching something private, and at times the camera is clearly handheld. It feels raw and real in a way many narrative films do not.

Repetition is really the key aspect of this film. The reappearance of dialogue, language, sound, symbols, scenes, and footage is vital for the film’s success. It never feels tired or lazy because it helps the audience to not only better grasp the large themes at hand, but it makes the audience truly understand the characters—at times, helping them understand what is going on or being said before the film has a chance to explain it.

Whether it be an illuminated alter in an otherwise dark church or the direction of a candle’s smoke or utter silence, there seems to be so much symbolism steeped into the film. But it never fails to move the audience’s understanding of the two characters and their connection.

As a priest told Francis during a flashback, “love has many faces” and this film is a testament to that. The film shows a deep and loving friendship form through long conversations and a willingness to change and understand each other, but also through humor and dance and music and prayer.

As priests, bishops, cardinals, and popes, these leaders in the Catholic Church are seen as closer to God. Maybe not as people, but in their ability to understand and communicate with him.

But “Two Popes” reminds us that these figures are just as human as everyone else. Their pasts are riddled with sin and compromise and mistakes they wish they could undo, yet they can’t. Just like us, they can only learn from their mistakes and change what they choose to do in the future.

Throughout the film it is Pope Francis that insists on not only forgiveness, but the ability to change. Yet it is Pope Benedict who reminds both Francis and the audience to “believe in the mercy you preach,” that you cannot have mercy for others and not yourself because “you’re not god, you’re only human.”