Story by Zoe Yu Gilligan

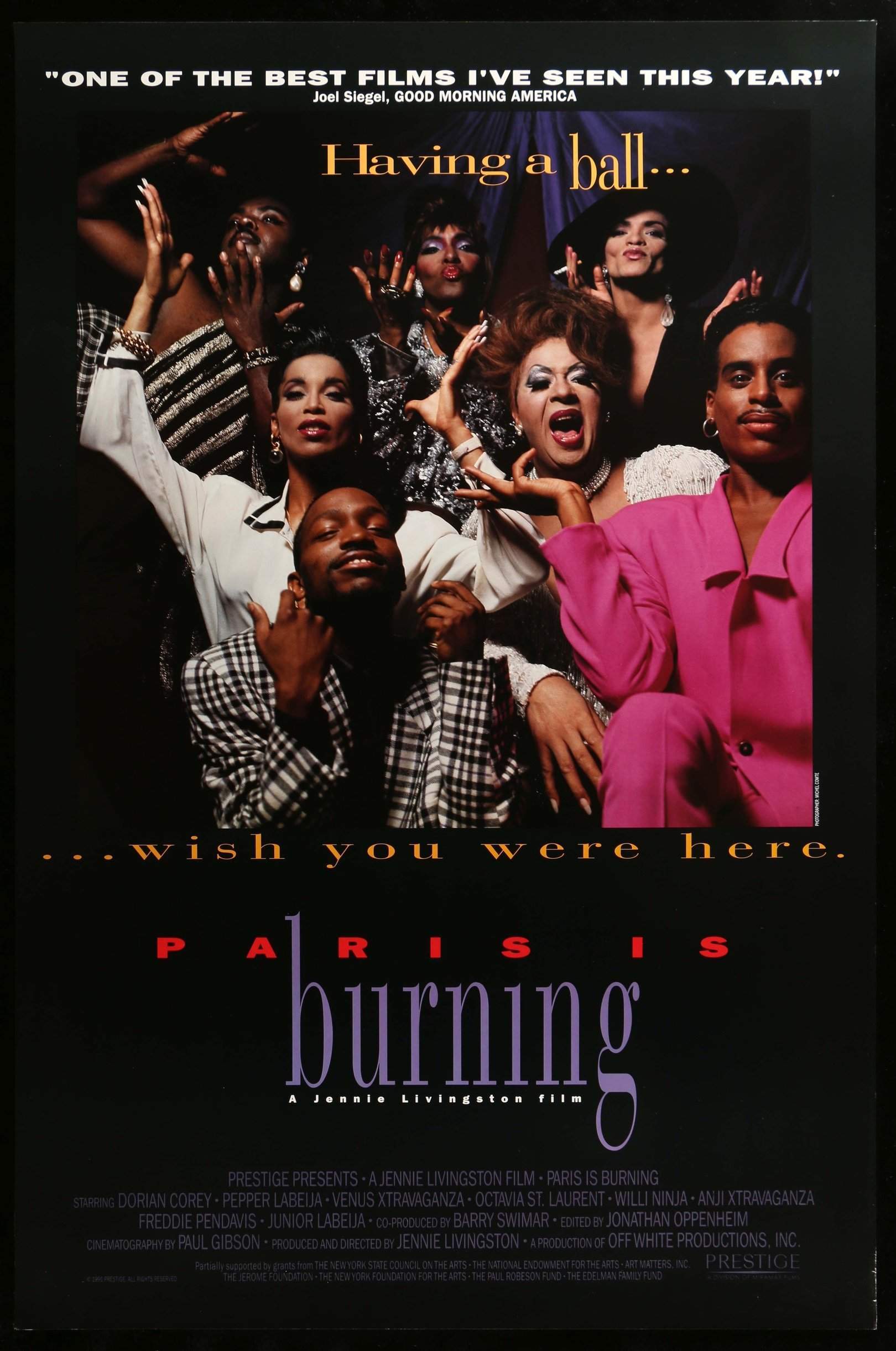

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, Film Forum in New York City and Landmark’s Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles have been screening Jennie Livingston’s “Paris is Burning”, a 1990 landmark documentary about the city’s “Golden Age” of ball culture in its last years. It won the 1991 Sundance Grand Jury Prize and was selected in 2016 for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. It is thought of to this day as one of the most important works exploring race, gender, sexuality, and class in America.

Livingston’s intimate portrait of Harlem ball culture—the product of gay, transgender, poor, and mostly Black and Latinx folks—shines a light on what is one of this country’s most influential subcultures. At these gatherings coined as balls, participants “walk” (compete) for trophies, prizes and distinction within the community, ultimately being whatever they wish to be for the night. They walk, dance and/or vogue in drag categories aimed at emulating different genders and social classes. They are judged on appearance, attitude, dance skills, and “realness”. By performing conventional gender roles of excess and wealth through their drag, participants simultaneously question these roles.

Ball culture also extends beyond balls, as many people belong to different factions known as “houses”, which imitate a family structure by having “mothers” or “fathers” who are the leaders of their respective houses. They recruit people to their houses to walk in balls, but these houses also serve as chosen families for many gay, transgender and gender non-conforming folks of color. Houses that win heaps of trophies are considered legendary and people who win them are also granted an irrevocable legendary status.

Some of the most famous houses were featured in Livingston’s documentary, such as the House of Ninja (founded by Willi Ninja), the House of Xtravaganza (founded by Hector and Angie Xtravaganza), the House of LaBeija (founded by Crystal LaBeija), and the House of Dupree (founded by Paris Dupree). House members typically adopt house names as their own last names.

It was a 1980s New York summer when Livingston was in Washington Square Park and met two young men who were voguing. She attended her first ball that summer at the Gay Community Center on 13th Street where she saw Venus Xtravaganza, one of the film’s subjects, for the first time. After that ball, she began to spend time with Willi Ninja, another of the film’s subjects, to learn more about ball culture and vogueing, as well as beginning to audio interview other ball participants: Venus Xtravganza, Octavia St. Laurent, Pepper Labeija, and Dorian Corey to name a few.

Film production took place during the rest of the decade, beginning with the Paris is Burning ball in 1986 and finally ending in 1989. The majority of the film spans between footage of balls and interviews with prominent people in the ball scene whose testimonies shed light on queer and ball culture, as well as on their own life stories. Many of them grapple with issues such as racism, poverty, HIV/AIDs, homelessness, violence, homophobia, and transphobia. The candid interviews offer insight into the strength of queer and transgender people of color (QTPOC) in 1980’s New York and how many of them were simply struggling to survive in “a rich, white world,” with their pride and humor still intact.

Along with drag, the film also documents vogueing’s origins and how Willi Ninja is seen as its innovator. Livingston uses dancing and ball culture as lenses to analyze the living conditions of the QTPOC community—how they strive to meet the demands of the media that is prejudiced against them in the first place and how they survive these trials with wit, ingenuity and dignity.

While favorable reviews were numerous at the time of its release, controversy surrounding the film extended beyond its content to its creator, Jennie Livingston. bell hooks notably criticized “Paris is Burning” for its colonial gaze, since Livingston is a white, middle-class, genderqueer lesbian who portrayed balls and blackness, in hooks’ opinion, as a spectacle to “pleasure” white audiences. Furthermore, hooks states that Livingston depicted womanness and femininity within ball culture as being totally personified by whiteness, that the ruling-class white woman, “adored and kept, shrouded in luxury,” is conveyed as the standard QTPOC should aspire to without any real critique of patriarchy.

Others share the sentiment that Paris has burned altogether. Once mainstream America benefited from its cultural appropriation, copying a marginalized subculture that was copying it in the first place, the subculture itself then became of disinterest to the mainstream. For instance, its lexical influence is present everywhere in our pop culture today—“fierce,” “shady,” “work,” “yasss queen”—yet we mostly do not recognize its origins in the ball scene. Ball culture’s legacy and impact often go uncredited, and thus the community remains largely invisible.

“People may not understand the hurt that was caused by ‘Paris is Burning’,” said Kevin Omni Burrus, an original cast member of the documentary, in an article for The Daily Dot. “Not all of us were drug addicts, thieves, or prostitutes. There were people with PhD’s and master’s degrees in the ballroom world. But [Livingston] just wanted to tell the broken part of the story. That’s what she built that film on.”

“Paris is Burning” is not perfect. It is limited and rudimentary. But it exists, even in a society that says this community should not exist at all, let alone have any media representation. It serves as a colorful time capsule and cultural artifact–an important reminder to never cease in political shrewdness with the media we consume. This is especially the case in 2019 in which there are so many people and initiatives from the community to support and uplift, whose respective stories and efforts are already changing the perceptions left behind from Livingston’s documentary.

Queer history is American history. American culture wouldn’t exist without QTPOC and it’s vital we honor these stories and people. As a non-white ally myself living in New York City, I urge the rest of us to be critical of rainbow capitalism and honor Pride’s true origins beyond the month of June, to recognize the insidious effects of our silence and complacency, and to continually be militant against homophobia and transphobia. Stonewall was a riot against the state. Since 1969 and then later since the time of “Paris is Burning”, violence against transgender women of color still flourishes.

In remembrance of Venus Xtravaganza whose murder was never solved (suspected to be by a disgruntled client), Layleen Polanco Xtravaganza who was recently found dead in her Rikers cell, Jennifer Laude who was murdered by a nineteen year-old U.S. Military Officer in the Philippines, and the other countless Black, Latinx and Indigenous transgender women who have been murdered this year and every year before it, we will Say Her Name. We will say all of their names because Trans Lives Matter and Trans Black Lives Matter.

Paris may have burned but we allies still have all the support and resources to share, so if we are not standing with the community and centering them in our solidarity work, we are actively countering everything do.

The screenings at Film Forum and the Nuart Theatre have run from Pride Month and will conclude this Thursday July 11. “Paris is Burning” otherwise is available on Netflix U.S. for viewing.