Story by Taylor Stout

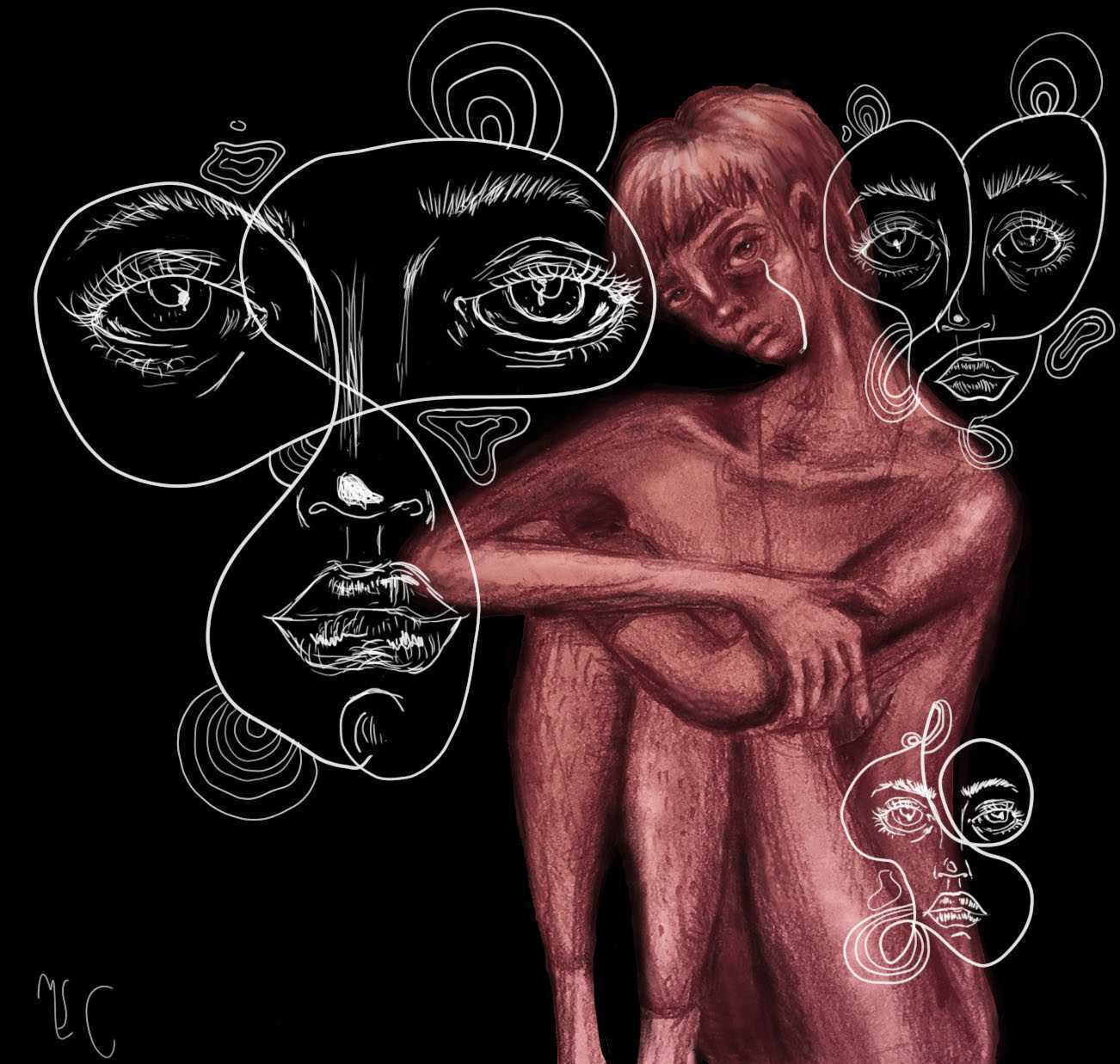

Illustration by Maya Cardinali

It’s difficult to pinpoint the moment my life changed. Maybe it was the day I received my letter of admission, or when I moved into my dorm room, or attended my first class. My memories of my freshman year of college are so shifting and vivid that I can barely comprehend them collectively. These months passed quickly. When they were over, I was struck by a feeling of breathless exhilaration, of not understanding quite what it was that had just hit me. Yet, if I try to place myself back in the shoes of that eighteen-year-old stepping on to a city street that I could for the first time call my own, wearing the necklace my father gave me for good luck, I am blocked by a feeling of distance. Time has created a veil between who I am and who I was about a year ago, and despite the arbitrary nature of the events that compose its fabric, it is impenetrable.

Through the months when everything seemed to be in flux, there was one constant: I carried Elif Batuman’s 2017 novel “The Idiot” almost everywhere I went. I read it in fragments while sitting on park benches, waiting in lecture halls, lying on my bed, and resting on a lawn by the Hudson River on one of the first days of spring. It was the one thing that seemed to reflect what I was experiencing.

The novel follows a young woman named Selin as she begins her freshman year at Harvard in 1995. Her college experience plays out parallel to her experiments with the new technology of email — somewhat inadvertently, she begins corresponding with an older student, and her token “love interest,” Ivan. The novel itself is at once hilarious, enchanting and strikingly realistic. Selin is simultaneously foolish and whip-smart. When she first receives an ethernet cable, she asks, “What do we do with this, hang ourselves?” Sardonic humor aside, she perceives the world through its minute details, such as the beauty of “watching someone you’re infatuated with fish something out of a jeans pocket,” or biting into a croissant that alone “makes you feel cared for.”

Over the course of my own freshman year, I followed Selin’s story as she struggled to choose a course of study, contemplated the boundaries of language as she corresponded with Ivan, travelled to Hungary to teach English over the summer, and, after everything, arrived at the conclusion that she had learned absolutely nothing. After the school year and its subsequent summer, Selin declares that her life “no longer seemed like a movie,” and when reflecting on her state of being, concludes, “I didn’t really know how to do anything real.” To an at once ambitious and confused young adult, these feelings of futility and passivity are all too familiar. This may at first sound self-defeating, but to me, it is the novel’s most meaningful point: sometimes we aren’t even aware of the ways in which life is changing us.

The novel’s epigraph, a quotation from Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time,” reads, “In later life we look at things in a more practical way, in full conformity with the rest of society, but adolescence is the only period in which we learn anything.” Selin is not immune to this, and despite her own beliefs, she does learn over the course of the novel. The issue is not her perceived inertia, but that she cannot comprehend the ways in which these changes have taken effect. “The Idiot” follows its protagonist across a period of transformation, and the transformation occurs not in the profound, but in the mundane: the obsessively re-read message, the meandering summer job, the dorm room Joni Mitchell-listening sessions with friends. It weaves everyday details and internal monologues into narrative.

I finished “The Idiot” around the time I was taking my finals for the spring semester. I didn’t know quite what the year would add up to. I had had a great time, but like Selin, I wondered if I had learned anything “real.” All I know is that I am different now, although I cannot really say how. Only a year has passed, and I already look back on certain moments and wonder how I could have been both so earnest and so stupid. But this discomfort shows that I have learned. To be on the cusp of adulthood can be terrifying, and this is exacerbated by the impossibility of knowing when and what one is supposed to be learning. Maybe that’s why I can’t find the moment my life changed — it wasn’t a single moment, but a series of everyday experiences that led me to myself when I wasn’t even paying attention. Maybe, then, an idiot is a wonderful thing to be.