Story by Sara Radin

I have an immense fear of death and dying. Whenever I hear anything related to death, I immediately freeze up, and a wave of uncomfort passes over me. Moreover, I regularly experience existential crises, which jolt me out of the present moment and remind me of one very harsh reality: that I, and everyone I know and love, am going to die someday. And it could be any of us. Any minute now.

It’s no wonder that when I came across the book, “What to Do When I’m Gone,” written and illustrated by mother/daughter duo Suzy Hopkins and Hallie Bateman, I was immediately drawn to it. Born out of Bateman’s anxiety over the frightening acknowledgement that she will lose her mother one day, the book offers a deeply personal set of instructions for what she can do in the days, months, and years following the eventual loss, as written by her mother herself.

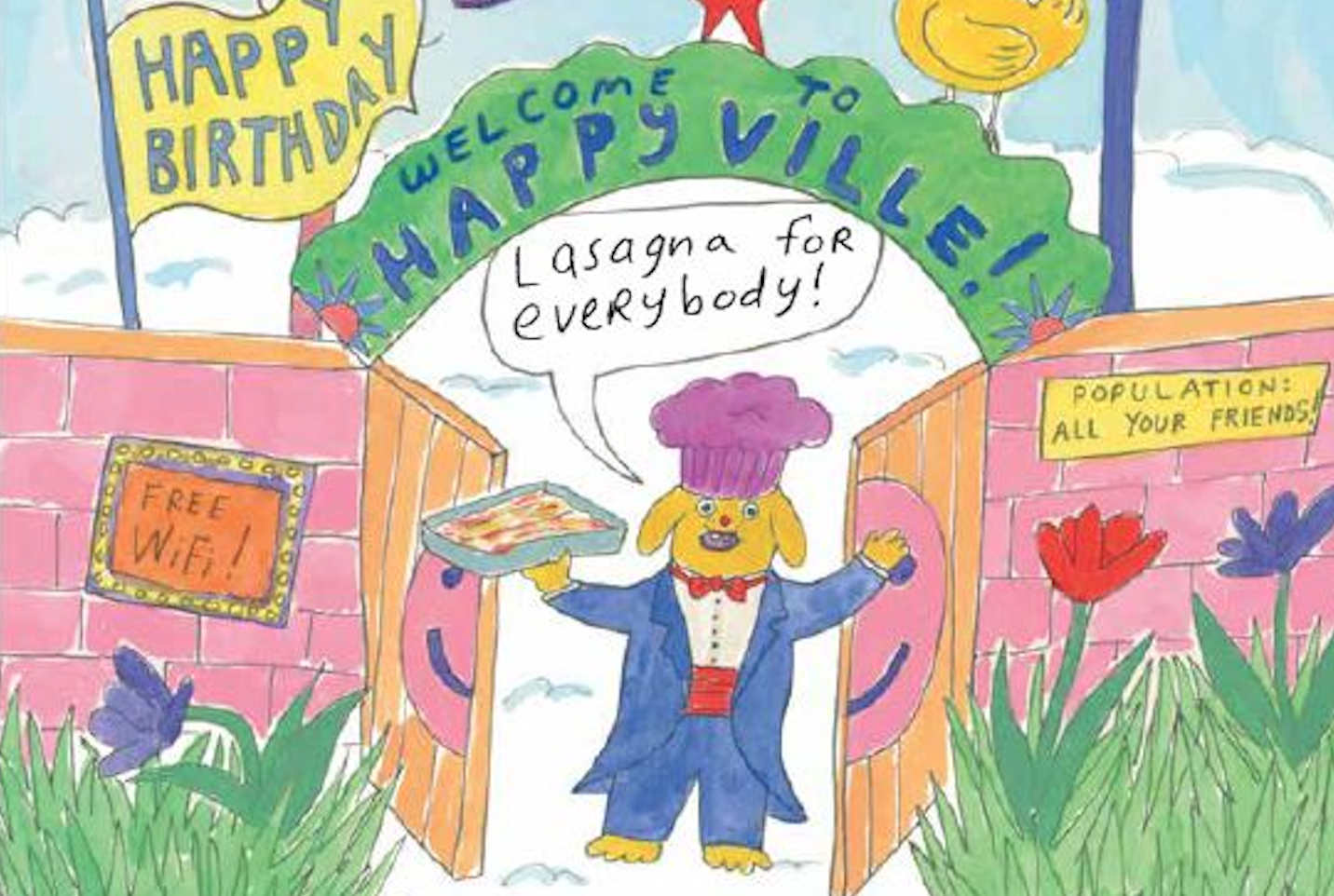

Released in April 2018, the book offers loving guidance to Bateman, who created all of the corresponding illustrations, which anyone can all relate to when addressing issues large and small, such as choosing a life partner to baking a quiche. In a time when talking about death is still largely taboo and grief is often experienced behind closed doors, the book confronts loss with soft humor, appreciation, and warmth, making everyone who reads it both laugh and cry. It is guidebook to grappling with death that teaches us to honor our loved ones even after they’re gone, which I plan to keep on my bookshelf forever.

Crybaby sat down with Suzy and Hallie to hear more about how the project came about, their experience as mother-daughter collaborators, and how making the book changed their perception of losing a loved one.

How did the idea for the book come about?

Hallie: When I was 23 and visiting my parents, I had a sleepless night where I imagined losing my parents. I let myself imagine, in detail, how it would feel to lose my mother. My mom and I are very close, and it really struck a chord. I felt I’d be paralyzed without her. I imagined myself unable to function, make basic decisions, without her. The next morning, while we made breakfast, I asked my mom (a writer herself) to make me a book of instructions for what to do, starting the moment after she dies. She loved the idea.

Suzy: I’ve long thought that families don’t talk enough about death even though it’s a universal experience as central in our lives as birth. So I thought it was a great idea. And I want to leave my children some thoughts and ideas, a trace of me.

What was your process for making this book happen?

Hallie: It took about five years from the time we started talking about it to actually do it. My mom and I took a trip together to Maine and holed up in a little cabin. I brought my laptop and said, “we’re writing the book.” I started to ask her questions — “Okay, you just died. What do I do?” and she talked and I typed. We left the cabin with a first draft and continued to work on it over the next eight months or so. We wanted to write the whole thing before getting a publisher involved so that we could make it exactly what we wanted for ourselves, first.

Suzy: Initially I thought of this just as a family project. But after a couple of days, we realized that the questions and ideas we were discussing were universal in nature. We began to think that other people might relate to the topics at the heart of it.

What was it like collaborating as a mother-daughter duo? Was it your first time doing a project together? Do you think you’ll do another project together in the future?

Hallie: In my early twenties, I illustrated one of her teenage journal entries, which was wonderful, but we’ve never worked on anything as ambitious and collaborative as “What To Do When I’m Gone”. It was incredibly challenging and incredibly rewarding. My mom is as funny as she is wise, and we laughed a lot in writing it. We’re both super driven and were evenly matched in our work ethic. But we definitely fought and had disagreements. I’m so used to controlling everything about my projects, it was tough to let go and allow my mom the creative space she needed — and the time for her to understand how the illustration was going to fit into it. I was a brat sometimes, but she didn’t seem to be phased by my occasionally bad attitude. She never doubted us. She always thought the book was wonderful, even when I was surly and believed that nobody would understand it.

Suzy: Any mom whose close with her daughter might relate to how I felt: When they leave home, you miss that regular, in-person contact. Our conversations about the book were so interesting and intimate, it felt nourishing for me: I got my “daughter” fix every day. It was the first time we’d worked together, and I have a different and certainly slower working and thinking style. Hallie moves at lightning speed, while I take time to ponder before committing thoughts to paper. It was important to me to only leave advice that I felt was very true to my beliefs, and she came to understand that, while I learned about her abilities and thought processes related to illustration and its relationship to narrative. And yes, I would love to do another book with Hallie.

This book touches on fear, loss and grief, which are things we don’t really talk about enough in public spaces. Did the practice of making this book bring up any challenging emotions for either of you? If so, how did you cope with that?

Hallie: Weirdly, I think I set a lot of my emotions aside while we wrote. I think I had to, in order to get it done. I operated off of this memory of that night when I was 23. I held that feeling very tightly but didn’t really emote. It was like data, if that makes any sense. But there were absolutely days when we were writing that it really sunk in what we were doing and it hit hard. It felt extremely urgent. Not because my mom was sick or anything, she’s totally healthy. It just felt necessary to talk about it. To spend time together and discuss the inevitable. I felt I was doing a service to my future self and to my brothers.

Suzy: Writing the scene about the first birthday Hallie will celebrate without me was particularly emotional. It was the first time I really came face to face with my own mortality. I realized in a heartbeat how many special moments in her life, and in the lives of my sons, that I will miss.

How did this book change how you feel about the loss of a loved one?

Hallie: It’s still something I know will be really hard. It didn’t erase my fear of losing my mom, but I do feel a huge sense of safety that we created our own handbook for this thing that there’s no handbook for. And even more importantly, we had the experience of writing it together. I got to ask her about everything.

Suzy: I understood grief more clearly, and what an enormous passage it is to new understanding. It made me feel more grateful for the time I have with the people I love.

Why did you choose to approach death with such a humorous and honest tone of voice?

Suzy: I’ve always found that humor helps take some of the sting out of difficult times — times of sadness and uncertainty. And I believe honesty is everything, both in relationships and when communicating with others on difficult topics or during hard times.

What were some of your favorite instructions to write or draw out?

Hallie: I loved painting the full-page illustrations. In my previous work I’ve mostly made line drawings, messy and loose. It was such a huge shift to work in gouache and create detailed backgrounds for each illustration. “Brush the dog” is one of the ones I’m most proud of. I just love how the colors came out, and of course my mom’s writing.

Suzy: I love so many of them, but in particular, the opening scene of the grieving girl and cat on a couch, and later on, the recipe illustrations, which remind me of happy times when my kids and I cooked together.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

Hallie: It sounds weird to say, but when people tell me they cried reading it, I feel so honored and touched. From our earliest draft, we wanted our book to do that — to allow people to cry not out of fear or sadness, but out of pure catharsis. Out of awareness.

Suzy: I hope it comforts readers who have lost or are losing a loved one. And I hope it sparks conversations in families, about a parent’s thoughts on death and dying, and what memories and family history they want to leave for their children.

What do you wish you knew about death when you were younger?

Hallie: I never knew my grandfathers, and my grandmothers were both quite old when I was growing up, and passed away before I got to know them very well. I wish I’d been able to talk to them more honestly, to let my guard down and be myself with them. I feel like I lost an opportunity to know them by trying to be a proper and polite granddaughter, and not wanting to be anything but pleasant around these fragile old women. I wish I’d known to be less wary and just try to connect.

Suzy: That it is inevitable. (Denial is a powerful force; when I was young I thought death might pertain to other people but perhaps not to me). And knowing that, spend your time wisely.